Listening to Trees: The Art of Ecological Perception

Sara Srifi

Fri Oct 31 2025

Learn to listen to trees through ecological perception. Explore tree communication science, observation skills & Indigenous wisdom for environmental awareness.

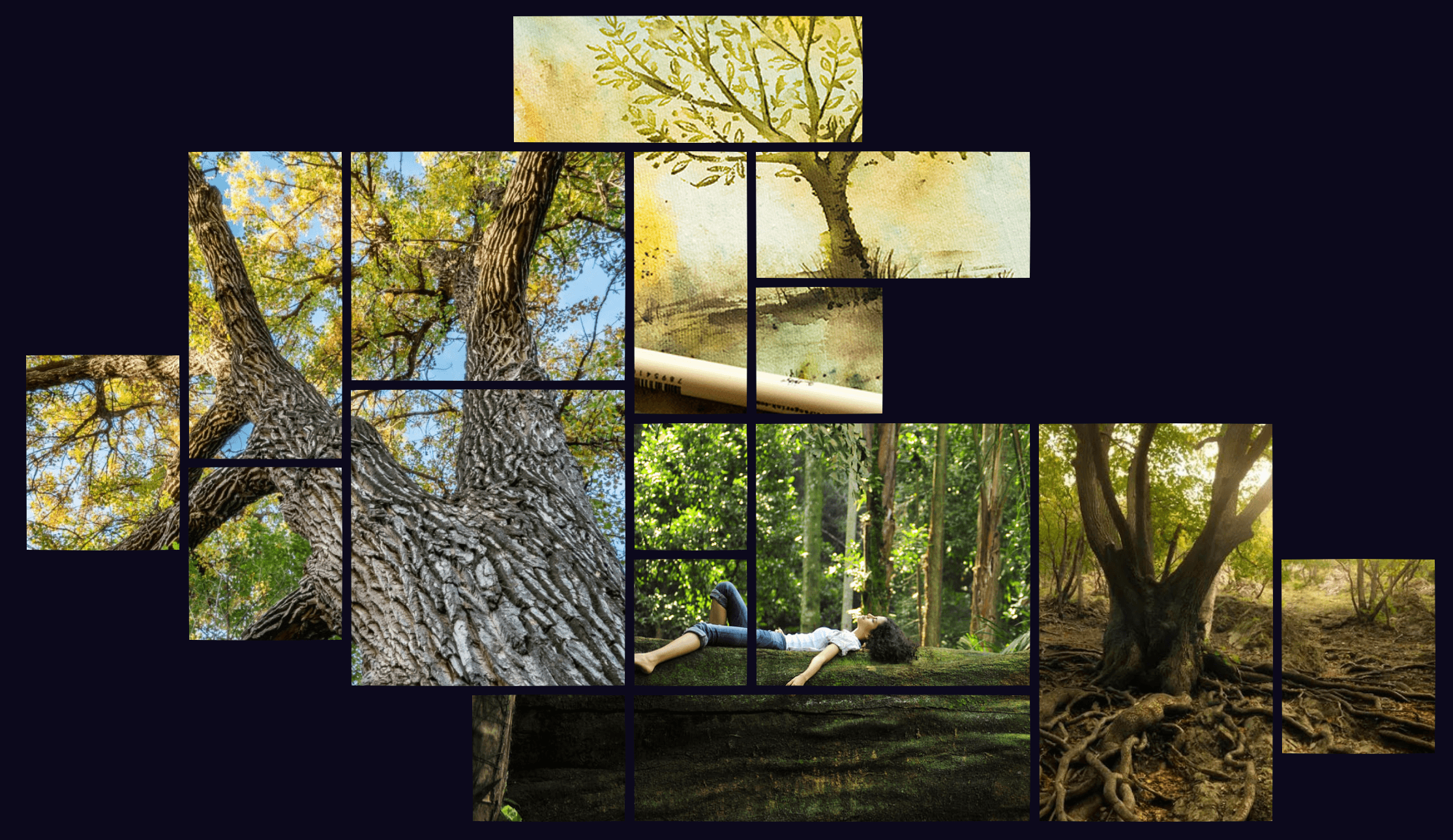

In an age dominated by screens and digital noise, we've largely forgotten how to listen to the natural world around us. Trees, the silent giants that have witnessed centuries of human history, communicate in ways we're only beginning to understand. Learning to perceive these ecological conversations isn't just poetic romanticism, it's a scientifically grounded practice that can deepen our connection to nature and inform environmental stewardship.

What Does It Mean to "Listen" to Trees?

Listening to trees extends far beyond the rustling of leaves in the wind. It encompasses a multisensory approach to understanding forest ecosystems through observation, pattern recognition, and scientific inquiry. This practice combines Indigenous wisdom traditions with modern ecological science, creating a holistic framework for environmental perception.

Trees communicate through chemical signals, fungal networks, sound vibrations, and visual cues. By developing our capacity to observe and interpret these signals, we cultivate what ecologists call “ecological literacy”, the ability to read landscapes as living, interconnected systems.

The Science Behind Tree Communication

Recent research has revolutionized our understanding of how trees interact with their environment and each other. The "wood wide web," a term coined to describe underground fungal networks, allows trees to share nutrients, water, and chemical warning signals across vast distances. Mother trees can recognize their own offspring and preferentially allocate resources to help young seedlings establish themselves.

Trees also respond to sound vibrations. Studies show that roots grow toward the sound of running water, and some research suggests plants may produce ultrasonic clicks as they transport water through their vascular systems. These discoveries validate what forest dwellers and Indigenous peoples have long known: trees are far more dynamic and communicative than Western science traditionally acknowledged.

Developing Ecological Perception Skills

Observation and Patience

The foundation of listening to trees begins with slowing down. Spend time sitting quietly with a single tree or in a forest grove. Notice the bark texture, branching patterns, and the community of organisms living on and around the tree. Over multiple visits, you'll begin to perceive seasonal rhythms, growth patterns, and the tree's relationship with its neighbors.

Engaging Multiple Senses

Move beyond visual observation. Touch the bark and notice temperature variations. Listen for the sound of wind moving through different leaf shapes—oak leaves rustle differently than pine needles. Smell the volatile organic compounds trees release, especially after rain or when under stress. These sensory inputs build a comprehensive picture of tree life.

Learning Tree Indicators

Trees are excellent environmental reporters. Lichen growth patterns indicate air quality. Leaf color and timing reveal climate patterns. Bark scarring tells stories of past fires, animal activity, or human interference. Crown shape reflects competition for light and past weather events. Learning to read these indicators transforms trees into historical archives and environmental sensors.

Indigenous Wisdom and Traditional Ecological Knowledge

Indigenous communities worldwide have practiced deep ecological listening for millennia. These knowledge systems recognize trees as relatives and teachers, not resources. Practices like the Anishinaabe concept of "listening to the land" or the Aboriginal Australian understanding of Country as a living entity offer profound models for developing ecological perception.

Traditional ecological knowledge emphasizes reciprocity, the understanding that observation comes with responsibility. When we learn to listen to trees, we inherit an obligation to protect and care for forest ecosystems. This ethical dimension distinguishes true ecological perception from mere nature appreciation.

Practical Applications for Environmental Education

Forest Bathing (Shinrin-yoku)

The Japanese practice of forest bathing provides a structured approach to developing tree awareness. By intentionally immersing ourselves in forest atmospheres, we reduce stress while simultaneously enhancing sensory perception. Studies show that time spent among trees lowers cortisol levels, improves immune function, and enhances cognitive performance.

Phenology Monitoring

Tracking seasonal changes in trees, bud break, flowering, leaf color change, leaf fall, connects us to ecological rhythms while generating valuable climate data. Citizen science projects like Nature's Notebook allow individuals to contribute observations that help scientists understand how climate change affects tree species.

Tree Journaling

Maintaining a regular journal about specific trees or forest patches develops observational skills and creates personal ecological narratives. Sketch bark patterns, note animal visitors, record weather conditions, and document your sensory experiences. Over time, these journals reveal patterns invisible in single visits.

The Role of Technology in Enhancing Perception

While deep listening requires unplugging, certain technologies can amplify our perceptual abilities. Bioacoustic monitoring equipment captures ultrasonic tree sounds humans cannot hear. Time-lapse photography reveals slow tree movements and growth patterns. Dendrochronology, the study of tree rings, unlocks climate histories spanning centuries.

AI-powered tree identification apps help beginners learn species quickly, though developing the skill to identify trees without digital assistance remains valuable. The goal is using technology as a bridge to deeper, eventually technology-independent understanding.

Challenges and Considerations

Urban environments present unique challenges for tree listening. Noise pollution, fragmented habitats, and limited species diversity constrain opportunities. However, even a single street tree offers lessons in resilience, adaptation, and urban ecology. Cemetery trees, park specimens, and protected old-growth fragments provide accessible listening posts in developed areas.

Climate change complicates tree reading as traditional patterns shift. Trees experience phenological mismatches, range migrations, and stress responses that challenge established ecological knowledge. This makes the practice of listening even more critical—we need skilled observers to track and respond to these changes.

Cultivating an Ecological Worldview

Learning to listen to trees fundamentally changes how we inhabit the world. It shifts our perspective from anthropocentric to ecocentric, from extractive to reciprocal. We begin recognizing ourselves not as separate from nature but as participants in ecological communities.

This perceptual shift has profound implications for environmental action. People who develop relationships with specific trees and forests become powerful advocates for conservation. Ecological perception transforms abstract environmental concerns into personal relationships worth defending.

Getting Started: A Simple Practice

Begin with one tree. Visit it weekly for a season. Notice everything: the ground beneath it, the creatures visiting it, the way light filters through its canopy, how it changes week by week. Draw it, photograph it, sit with it. Ask questions: How old might it be? What has it witnessed? What species depend on it? What can it teach you about this place?

This simple practice of devoted attention is the foundation of ecological perception. From this beginning, your capacity to listen will naturally expand to encompass forests, watersheds, and entire landscapes.

The Future of Ecological Listening

As environmental challenges intensify, humanity needs more people who can listen to trees—who can read landscapes, notice ecological shifts, and respond with informed action. This skill isn't reserved for scientists or Indigenous elders; it's a learnable capacity available to anyone willing to slow down and pay attention.

The art of ecological perception represents a crucial bridge between scientific understanding and embodied wisdom, between data collection and deep relationship. In learning to listen to trees, we recover an ancient human capacity while developing skills essential for navigating the environmental challenges ahead.

The trees are speaking. The question is: are we ready to listen?

Frequently Asked Questions

How do trees actually communicate with each other?

Trees communicate through multiple channels including underground fungal networks (mycorrhizal networks), airborne chemical signals called volatile organic compounds, and root-to-root contact. When under attack by insects, trees can release chemicals that warn neighboring trees to activate their own defenses. The mycorrhizal network also allows trees to share nutrients, water, and information across the forest floor.

Do you need special equipment to start listening to trees?

No special equipment is required to begin practicing ecological perception. Your senses—sight, touch, hearing, and smell—are your primary tools. However, as you advance, items like a hand lens for close observation, a field guide for species identification, a journal for recording observations, and a camera for documentation can enhance your practice.

How long does it take to develop ecological perception skills?

Developing basic observational skills can begin immediately, with noticeable improvements in just a few weeks of regular practice. However, deep ecological literacy develops over years of consistent engagement with forest ecosystems. Most practitioners find that spending 20-30 minutes weekly with the same tree or forest area for a full season provides a solid foundation.

Can you practice tree listening in urban environments?

Absolutely. Urban trees offer valuable lessons in resilience, adaptation, and ecology. Parks, botanical gardens, cemeteries, and even street trees provide opportunities for observation. Urban trees often face unique stresses that make their survival strategies particularly interesting to study. Start with whatever trees are accessible to you.

Is there scientific evidence supporting tree communication?

Yes, extensive peer-reviewed research supports tree communication. Notable studies by scientists like Suzanne Simard have documented nutrient sharing through mycorrhizal networks. Research has confirmed that trees respond to sound vibrations, recognize kin, and adjust their chemistry based on environmental threats. This field, sometimes called "plant neurobiology," continues to reveal sophisticated tree behaviors.

What's the difference between forest bathing and tree listening?

Forest bathing (shinrin-yoku) is a wellness practice focused on stress reduction and health benefits through immersion in forest atmospheres. Tree listening or ecological perception is a broader practice that includes sensory immersion but emphasizes learning to read, interpret, and understand ecological patterns and relationships. Forest bathing can be a gateway to deeper ecological perception.

How does climate change affect the practice of listening to trees?

Climate change is altering traditional tree behaviors—shifting bloom times, changing migration patterns, and creating new stress responses. This makes ecological observation more important than ever, as we need skilled observers to document these changes. It also means being humble about our predictions and staying open to unexpected patterns as ecosystems adapt.

Can children learn to listen to trees?

Children are often natural ecological observers with innate curiosity about the living world. Age-appropriate tree listening activities include bark rubbings, leaf collection, tree adoption projects, seasonal change tracking, and sensory exploration games. These practices build environmental literacy while fostering lifelong connection to nature.

Explore more about ecological awareness and environmental education with Wisdomia.ai's AI-powered learning tools designed to deepen your connection with the natural world.

previous

Learning as Transformation, Not Accumulation: A New Paradigm for Education

next

Classroom Practices That Nurture Reflection, Empathy, and Presence: A Complete Guide for Educators

Share this

Sara Srifi

Sara is a Software Engineering and Business student with a passion for astronomy, cultural studies, and human-centered storytelling. She explores the quiet intersections between science, identity, and imagination, reflecting on how space, art, and society shape the way we understand ourselves and the world around us. Her writing draws on curiosity and lived experience to bridge disciplines and spark dialogue across cultures.