Modern Revolutions and the Digital Explosion: Images That Shattered and Rebuilt Reality

Dinis GuardaAuthor

Wed Dec 17 2025

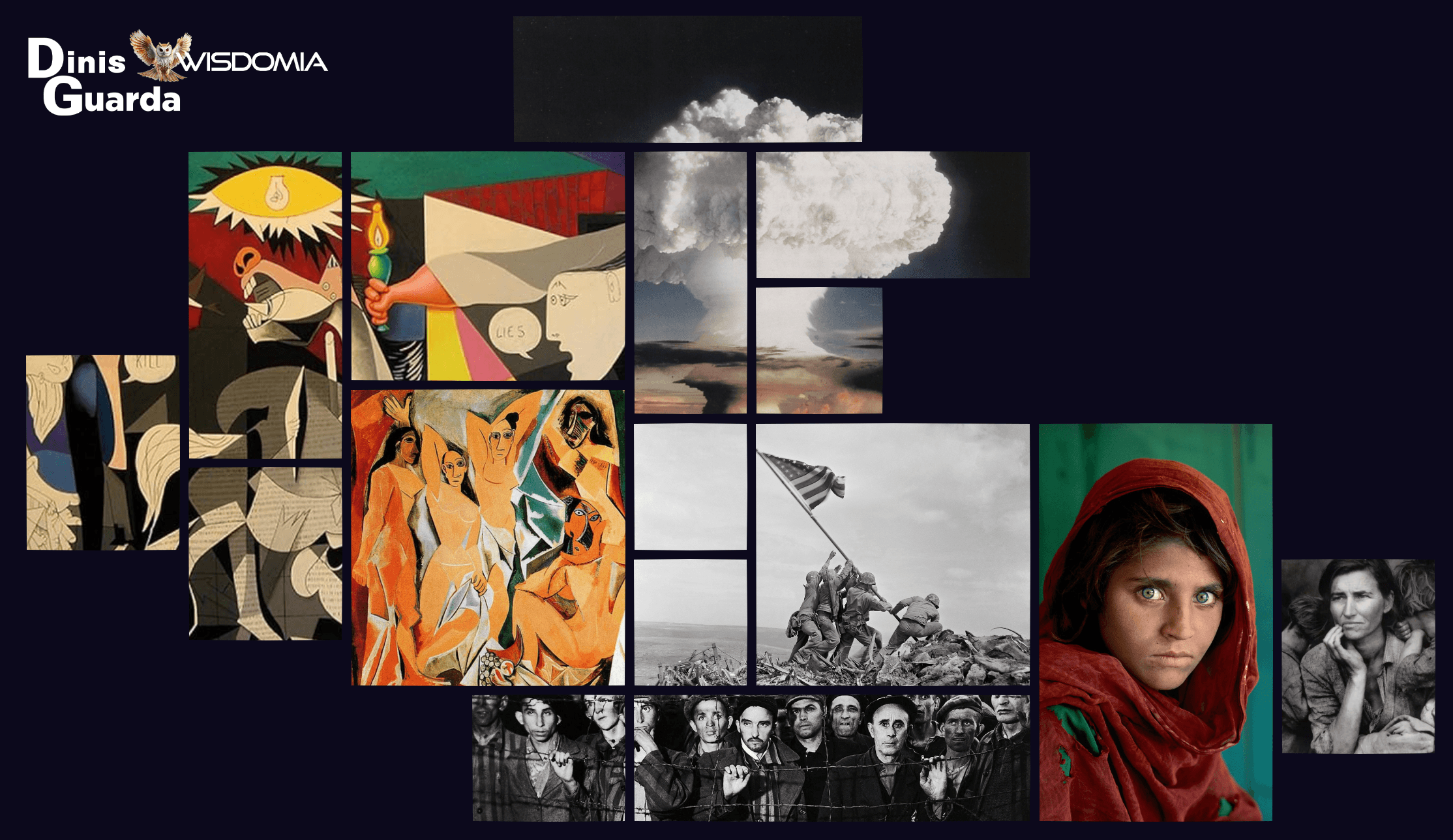

A powerful visual history of the 20th century, from Cubism and war photography to space images and digital culture, revealing how images stopped reflecting reality and began creating it.

From Cubism's Fractures to Instagram's Infinite Scroll: How the 20th Century Learned to See Everything, Everywhere, All at Once

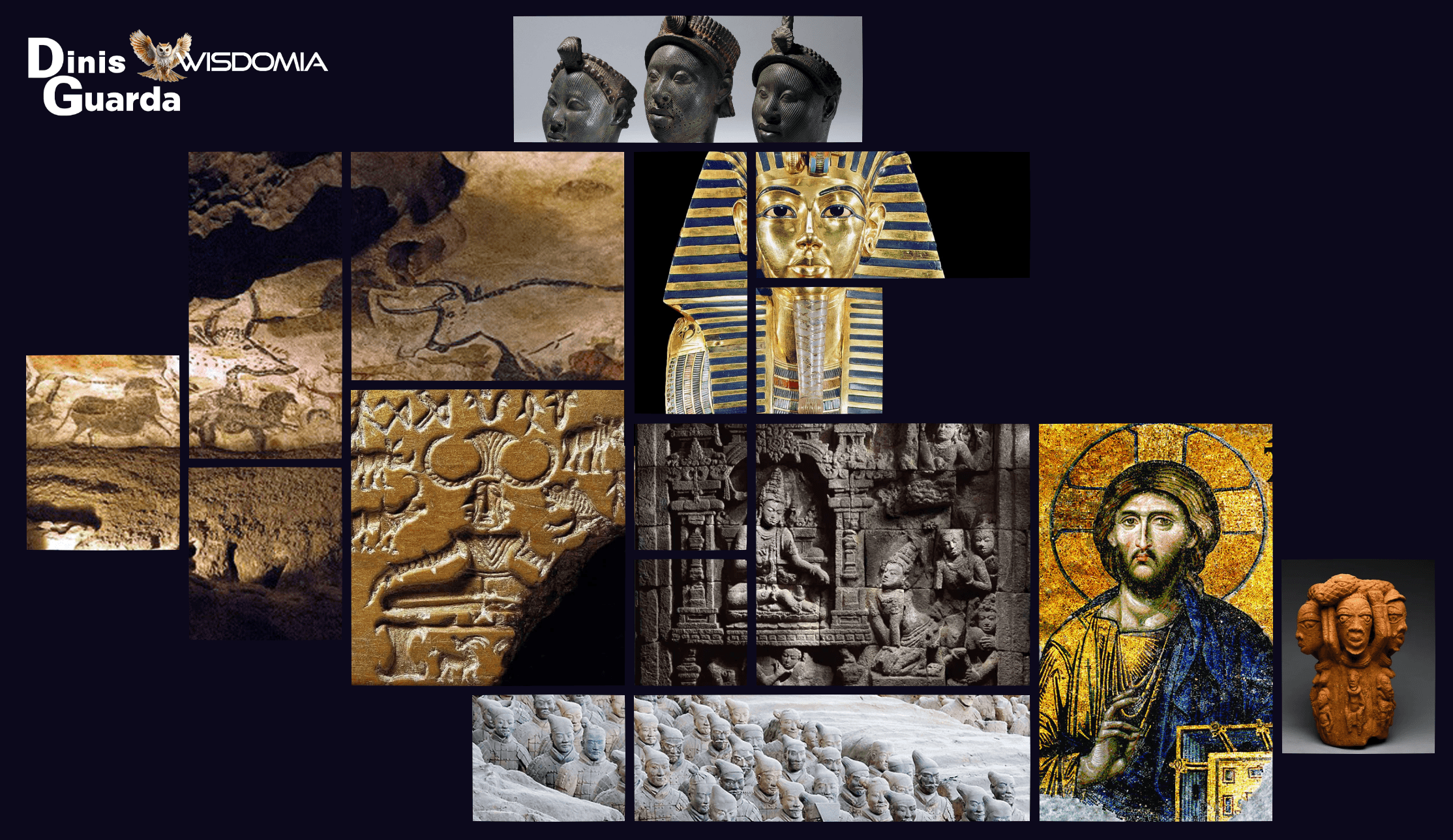

From “ The most Influential Powerful 100 Images in History of Humanity” mini-book By Dinis Guarda

The Century That Broke the Frame

The 20th century didn't just change how we make images, it exploded the very concept of what an image could be.

Between 1900 and 2000, humanity witnessed more visual transformation than in the previous 40,000 years combined. We fractured perspective (Cubism), negated representation (abstract art), mechanized reproduction (cinema, television), weaponized images (propaganda), documented unprecedented horror (Holocaust, Hiroshima), escaped Earth's gravity (Apollo photographs), and finally digitized vision itself (pixel replacing pigment, screen replacing canvas).

By century's end, the image had become humanity's primary language. We communicate in photographs, emojis, memes, videos. Children learn to swipe before they learn to write. Reality itself competes with its representations, we photograph experiences rather than experiencing them, curate identities through image streams, wage wars broadcast in real-time.

This transformation begins with five Parisian prostitutes whose faces would change art forever.

These 25 images (51-75) chronicle the 20th century's visual revolution: modernism's assault on representation, photography's documentation of atrocity, humanity's first self-portraits from space, and the early tremors of digital transformation. We witness art becoming concept rather than object, images becoming evidence of crimes against humanity, and ultimately the moment when images escaped human control entirely, proliferating, mutating, circulating faster than consciousness could comprehend.

The stakes escalate dramatically. Pre-20th century images required skill, resources, patronage. By 2000, anyone with a phone could create and globally distribute images instantly. The democratization photography began became universal. But democratization brought new problems: manipulation, propaganda, surveillance, the image as weapon.

We stand now at the threshold of artificial intelligence creating images indistinguishable from photographs, of virtual realities more compelling than physical experience, of a world where the line between image and reality has dissolved entirely. But that transformation was made possible by these 25 images, each one expanding what images could do, what they could say, what they could destroy or create.

The journey from Picasso's brothel to Instagram's global village is a journey from representation's death to its resurrection in forms the Renaissance couldn't imagine. Along the way, images documented humanity's worst atrocities and greatest achievements, our capacity for both sublime beauty and incomprehensible cruelty.

This is the century we learned that images don't just show reality, they create it.

MODERN REVOLUTIONS: When Art Exploded Reality (1900-1950)

51. Pablo Picasso - "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon" (1907)

Location: Museum of Modern Art, New York

Medium: Oil on canvas (243.9 × 233.7 cm)

Five nude prostitutes from Barcelona's Avignon Street stare with primitive mask-like faces (influenced by African art Picasso saw in Paris ethnographic museums), bodies fragmented into geometric planes.

Picasso broke perspective, broke the human figure, broke representation itself. Braque saw it and collaborated with Picasso to invent Cubism. This painting is modernism's ground zero.

Picasso visited the Trocadéro ethnographic museum in Paris, seeing African masks and sculptures that European colonialism had plundered and displayed as "primitive" curiosities. He recognized what academics couldn't: these were sophisticated aesthetic systems, not evolutionary stages toward European realism.

The five prostitutes confront viewers with aggressive sexuality and formal violence. Their faces are masks,two clearly African-influenced, angular and abstract. Their bodies fragment into geometric planes that ignore classical anatomy. Space collapses; perspective shatters; multiple viewpoints coexist impossibly.

This wasn't just stylistic innovation, it was philosophical revolution. Renaissance perspective assumed single viewpoint, rational observer, coherent space. Picasso destroyed those assumptions. Reality isn't singular or stable, it's fractured, multiple, simultaneous. Cubism would make this explicit, showing objects from multiple angles at once.

The painting scandalized even avant-garde artists. Matisse considered it mockery of modern painting. Critics called it ugly, incomprehensible, obscene. Yet within years, Cubism became modernism's foundation. By fracturing representation, Picasso liberated painting from the tyranny of resemblance. If images didn't need to look like reality, they could be anything.

The title itself is sanitized, Picasso originally called it "The Brothel of Avignon." Museums preferred euphemism, but the painting's confrontational sexuality remains. These women aren't passive nudes for male pleasure, they're aggressive presences demanding recognition.

52. Marcel Duchamp - "Fountain" (1917)

Location: Original lost; multiple replicas in museums

Medium: Porcelain urinal (signed readymade)

Duchamp submitted a urinal to an art exhibition, signed it with a pseudonym "R. Mutt," titled it Fountain, and asked: "What is art?"

Rejected by the exhibition, it became the 20th century's most influential artwork. Duchamp proved art is context, not craft; concept, not object.

Duchamp bought a mass-produced Bedfordshire urinal, turned it 90 degrees, signed it "R. Mutt 1917," and submitted it to the Society of Independent Artists exhibition (which claimed to accept all submissions). The board rejected it, calling it immoral and plagiarized (since it was manufactured, not handmade).

Duchamp (secretly on the board) resigned in protest. He photographed the urinal before it disappeared, ensuring its survival through documentation. The original was lost or destroyed; what we have are replicas authorized by Duchamp decades later.

Fountain asks: If an artist declares something art, is it art? Does artistic intention matter more than skill? Is beauty necessary? The urinal isn't transformed physically, it's the same industrial object. Only its context changes: from plumbing to pedestal, from functional to conceptual.

This gesture haunts art ever since. Every conceptual artwork, every readymade, every dematerialized piece descends from this urinal. Duchamp demonstrated that art happens in viewers' minds, not objects' properties. The "art" is the idea, the question, the provocation, not the thing itself.

Critics have debated whether Fountain is art's liberation or its death. Both are true. By making anything potentially art, Duchamp destroyed traditional hierarchies while creating infinite possibility. The urinal is simultaneously art's gravestone and its resurrection.

53. Kazimir Malevich - "Black Square" (1915)

Location: Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow (original); multiple versions

Medium: Oil on linen (79.5 × 79.5 cm)

A black square on white ground, painting's degree zero. Malevich exhibited it in the corner where Orthodox icons traditionally hang, replacing God with geometric abstraction.

He called it Suprematism: pure feeling, zero form. Stalin's regime suppressed it as degenerate; post-Soviet Russia resurrected it as prophetic.

Malevich painted Black Square for the 0.10 Exhibition in Petrograd (1915), hanging it in the corner traditionally reserved for religious icons. This wasn't accident, it was deliberate sacrilege and spiritual declaration. The square becomes new icon: not representing divinity but embodying pure abstraction.

Suprematism, Malevich's movement, sought art's liberation from representation. No objects, no narrative, no reference to visible world, only pure geometric form and color relationships. Black Square is the endpoint: even color minimized to black/white binary. Nothing remains except the essential gesture: mark on surface.

Yet the painting isn't actually a perfect square, and the black isn't purely black, underlying colors peek through cracks. Technical analysis reveals Malevich painted over other images. Even "pure" abstraction contains history, accident, materiality. The ideal can't fully escape the real.

Soviet authorities considered Suprematism bourgeois formalism, dangerous abstraction distracting from Socialist Realism's propaganda purposes. Malevich was marginalized, forced to return to figurative work. When he died (1935), Black Square was hung on the wall behind his body, icon accompanying him to whatever comes next.

The painting predicts minimalism, monochrome painting, conceptual art. It asks: What is painting's essence? When everything representational is removed, what remains? Malevich answered: the act itself, consciousness confronting surface, void made visible.

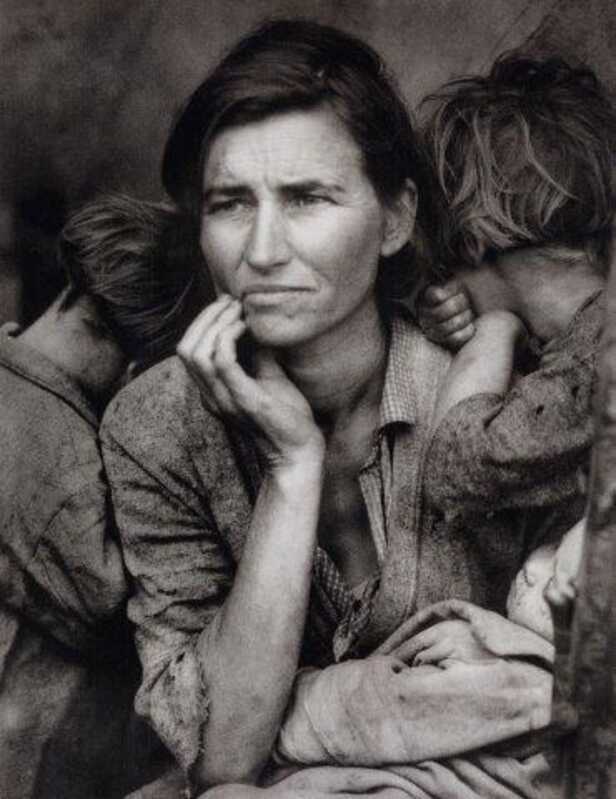

54. Dorothea Lange - "Migrant Mother" (March 1936)

Location: Library of Congress

Medium: Gelatin silver print photograph

Florence Owens Thompson, 32, sits in a lean-to tent with her children, her face etched with worry, her hand touching her face. Lange took six shots in ten minutes at a California pea-pickers' camp during the Great Depression.

The image became the Depression's icon, dignity amid destitution.

Lange was documenting rural poverty for the Farm Security Administration. Driving through California, she passed the pea-pickers' camp, drove on, then turned back: "I was following instinct, not reason." She approached Thompson's tent, took six photographs in increasing intimacy, never asked her name.

Thompson later said she regretted allowing the photographs, felt exploited. She never received payment while Lange built her career on the image. This tension haunts documentary photography: whose story is this? Who benefits? Thompson's children contacted Lange decades later seeking compensation; Lange had none to give, the image belonged to the federal government.

Yet the photograph's power is undeniable. Thompson's face contains multitudes: exhaustion, determination, fear, strength. She stares past the camera, calculating survival. Her children lean against her, faces hidden, demonstrating both dependency and trust. The composition is classical, mother and children, secular Pietà.

The image mobilized public support for federal relief programs, visualizing poverty's human cost. Thompson became the Depression's face, though she remained anonymous for decades. When identified in 1978, she was bitter: "That's my face. I can't get a penny out of it."

This raises documentary photography's central ethical problem: images that advocate for the powerless often exploit them. The photographer gains recognition; the subject remains poor. Good intentions don't resolve this contradiction, they reveal it.

55. Robert Capa - "The Falling Soldier" (September 5, 1936)

Location: Various collections

Medium: Gelatin silver print photograph

A Republican soldier, Federico Borrell García, flings backward, rifle flying, at the instant of death during the Spanish Civil War. Or is it staged? Debate rages.

Either way, it became war photography's definitive image, death captured in mid-fall.

Robert Capa (born Endre Friedmann) was 22 when he photographed the Spanish Civil War. His image of a soldier at the instant of death, arms flung back, rifle flying, body falling, seemed to capture what was previously impossible: the transition from life to death, the moment the soul departs.

But questions emerged: How did Capa anticipate the exact moment? Why is the soldier alone on an open hillside during battle? Is this too perfect? Investigations suggest the image might be staged, though whether by Capa or by soldiers reenacting combat remains disputed.

The authenticity debate misses the point: the image's power doesn't depend on literal truth. It represents war's waste, death's random cruelty, the instant when history's grand narratives reduce to one body falling. Staged or spontaneous, the image testifies to war's reality.

Capa's motto: "If your pictures aren't good enough, you're not close enough." He photographed five wars, dying at 40 when he stepped on a landmine in Vietnam. His blurred D-Day photographs (1944) became iconic precisely because their imperfection conveyed chaos, perfect images would have seemed false.

The Falling Soldier established war photography's grammar: be there, risk death, capture the instant. Every combat photographer since works in Capa's shadow, trying to show what survivors would rather forget and civilians need to see.

56. Pablo Picasso - "Guernica" (1937)

Location: Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid

Medium: Oil on canvas (349.3 × 776.6 cm)

The Basque town of Guernica, bombed by Nazis supporting Franco, becomes a monochromatic nightmare of screaming horses, dismembered bodies, light bulbs as suns.

Picasso painted it for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris World's Fair. A tapestry copy hangs at UN headquarters; Colin Powell stood before it announcing Iraq War (2003), the ultimate anti-war painting used as backdrop for war declaration.

On April 26, 1937, Nazi German and Italian Fascist aircraft bombed Guernica, a Basque town with no military significance, for three hours. The goal: terror. Civilians died in hundreds; the town burned. News reached Paris; Picasso began painting immediately.

Working in his studio at furious speed, he created a 25-foot-wide monochrome scream. A bull stands over a woman holding a dead child. A horse writhes in agony, speared, tongue like a dagger. A fallen warrior clutches a broken sword. A woman burns in a building. A light bulb shines like an evil sun. Electric light and ancient suffering merge, modernity doesn't end atrocity; it mechanizes it.

Picasso used Cubist fragmentation to visualize psychological destruction: bodies pulled apart, perspectives shattered, space collapsed. This isn't photographic documentation, it's trauma made visible, history painted from inside the scream.

The Spanish Republican government displayed it at the Paris World's Fair, where millions saw it. Then Guernica toured worldwide, raising funds for Spanish refugees. Picasso declared it couldn't return to Spain until democracy was restored. It stayed at MoMA for decades, finally returning in 1981 after Franco's death.

When Nazi officer visited Picasso's studio and saw Guernica, he allegedly asked: "Did you do this?" Picasso replied: "No, you did." The painting testifies: this is what you wrought. A tapestry reproduction hangs at UN headquarters. When Colin Powell announced Iraq invasion (2003), staff covered it, too inconvenient, this anti-war masterpiece, during pro-war propaganda.

WORLD WAR II & POST-WAR: When Horror Demanded Documentation (1939-1970)

57. Joe Rosenthal - "Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima" (February 23, 1945)

Location: Iwo Jima

Medium: Photograph

Six Marines raise the American flag atop Mount Suribachi. This was actually the second flag-raising (the first flag was too small); three of the six men died before the battle ended.

It won the Pulitzer Prize, became a postage stamp, inspired the Marine Corps War Memorial statue.

The image is almost too perfect: six figures straining together, flag unfurling at ideal angle, composition balanced yet dynamic. It doesn't look spontaneous, and it wasn't quite. This was the second flag-raising. A smaller flag went up first; commanders wanted a larger one for visibility. Rosenthal photographed the replacement raising.

This isn't "staged" (they were genuinely raising the flag under enemy fire), but it's not purely spontaneous either. The distinction matters for documentary ethics yet somehow doesn't diminish the image's power. The Marines are working together, bodies straining, flag rising, the image captures collective effort, not individual heroism.

Three of the six men died in subsequent fighting. The survivors became celebrities, touring America selling war bonds. One was Ira Hayes, a Pima Native American who struggled with being celebrated for killing Japanese soldiers while facing discrimination at home. He died alcoholic at 32, his life destroyed by fame arising from one photographed instant.

The image became the Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington. It's been reproduced millions of times, parodied endlessly, reduced to symbol. Yet it retains power: humans cooperating toward shared goal, victory's moment, nation's determination made visible. That the reality was complicated doesn't erase the image's meaning, it complicates it, makes it more human.

58. Margaret Bourke-White - "The Living Dead of Buchenwald" (April 1945)

Location: Buchenwald concentration camp, Germany

Medium: Photograph

Emaciated prisoners stare from their bunks, eyes hollow, bodies skeletal. Bourke-White was among the first photographers to document Nazi concentration camps' liberation.

She wrote: "I kept telling myself that I would believe the indescribably horrible sight before me only when I had a chance to look at my own photographs." Photography as evidence of atrocity.

Bourke-White arrived at Buchenwald with the U.S. Third Army in April 1945. She photographed systematically, barracks, bodies, survivors, perpetrators. Her photographs appeared in Life magazine, bringing Holocaust reality to millions of Americans who had read reports but couldn't comprehend scale until they saw images.

The survivors' faces haunt: not yet comprehending liberation, still trapped in terror's grip, bodies reduced to bones draped in skin. These aren't corpses, they're living humans barely surviving death. The photographs ask: How do we witness this? How do we continue after seeing this?

Bourke-White struggled with photographing suffering: "Using a camera was almost a relief. It interposed a slight barrier between myself and the horror in front of me." The camera becomes shield, distance mechanism, way to endure the unbearable by transforming it into task. Photography allows survival through documentation.

These images became evidence at Nuremberg trials. They circulated globally, making denial impossible. The Nazis had photographed their own crimes (meticulous bureaucrats documenting everything), but liberators' photographs served different purpose: testimony, evidence, warning. Never again, though "again" has happened repeatedly since.

59. Anonymous - "The Mushroom Cloud over Hiroshima" (August 6, 1945)

Location: Hiroshima, Japan

Medium: Aerial photograph

A mushroom cloud rises 20,000 feet above Hiroshima, containing 70,000 instant deaths and 70,000 more to come. The atomic age's birth announcement, humanity achieving godlike power to destroy itself.

Every nuclear photograph since quotes this composition.

The photograph was taken from the Enola Gay, the B-29 bomber that dropped "Little Boy" on Hiroshima at 8:15 AM. Tail gunner Bob Caron recalled: "A column of smoke rising fast. It has a fiery red core. A bubbling mass, purple-gray in color, with that red core. It's turbulent. Fires are springing up everywhere."

The mushroom shape became nuclear war's signature. Physics creates this form: the fireball's extreme heat causes air to rise rapidly, cooler air rushing in below, creating characteristic stem and cap. The beauty is obscene, this elegant form contains incomprehensible suffering.

Below the cloud: instant vaporization, shadows burned into stone, fires consuming wood and flesh, radiation beginning its invisible work. The photograph shows none of this, only the cloud, aesthetically striking, scientifically fascinating, morally horrifying.

Hiroshima changed everything. Humans could now end civilization, not gradually through war's accumulation but instantly through single weapons. The cloud represents threshold: before, only God could end the world; after, humans could. We achieved divine power without divine wisdom.

The photograph circulated globally, meaning different things: to some, American technological triumph; to others, humanity's fall; to Japanese survivors, their obliteration aestheticized. The image has been reproduced endlessly, becoming almost abstract symbol, we forget it contains actual deaths, actual suffering occurring at the instant the shutter clicked.

60. Alberto Korda - "Guerrillero Heroico" (Che Guevara) (March 5, 1960)

Location: Havana, Cuba

Medium: Photograph

Che Guevara at a memorial service, beret adorned with a star, gazing into distance with revolutionary intensity. Korda never got paid; the image became public domain, reproduced on T-shirts, posters, murals globally.

The most reproduced photograph in history, Marxist revolutionary transformed into capitalist commodity.

Alberto Korda was Fidel Castro's personal photographer. At a memorial service for victims of the La Coubre explosion (March 5, 1960), Che Guevara appeared briefly on the platform. Korda took two frames in seconds. Castro's newspaper didn't run the image; it seemed unremarkable.

Seven years later, Italian publisher Giangiacomo Feltrinelli requested images of Che for a poster. Korda gave him this photograph. After Che's death (1967), Feltrinelli printed thousands of copies. The image went viral (before "viral" existed), reproduced on protest posters, T-shirts, album covers, murals worldwide.

Che's expression, gazing past the camera with intensity and slight melancholy, seemed to embody revolutionary idealism. The composition is perfect: Che's face fills the frame, beret angled just so, star glinting, eyes focused on distant future. He looks like revolutionary saint, which is precisely how supporters remember him (and how critics mock the image's sentimentalization).

The irony is crushing: Che, devoted Marxist who despised capitalism, became capitalism's favorite image. His face sells everything, T-shirts, coffee mugs, cigarette lighters. Corporations profit from image of man who wanted to destroy corporations. Korda, believing in socialist ideals, never copyrighted the photograph. Che's face became public domain, free for anyone to commodify.

When Smirnoff Vodka used the image in ads, Korda sued successfully: "As a supporter of the ideals for which Che Guevara died, I am not averse to its reproduction by those who wish to propagate his memory... But I am categorically against the exploitation of Che's image for the promotion of products such as alcohol."

61. Henri Cartier-Bresson - "Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare" (1932)

Location: Paris

Medium: Gelatin silver print photograph

A man leaps over a puddle behind the Gare Saint-Lazare station; his reflection mirrors his suspended body. The "decisive moment" philosophy incarnate, Cartier-Bresson anticipated where the man would jump and clicked the shutter at the instant of perfect composition.

This image defines street photography: being present, anticipating action, capturing the instant when form and content align perfectly.

Cartier-Bresson called it “le moment décisif”, the decisive moment when visual elements align to create meaning greater than their sum. This photograph is his philosophy made visible: geometry (the man's body, his reflection, the ladder in background, circular ripples), motion suspended mid-leap, accidental grace captured.

The image is almost abstract: horizontal lines of wooden planks, vertical ladder, circular ripples, human figure frozen in mid-air. Yet it's intensely real, actual man jumping actual puddle in actual Paris. Form and content, abstraction and realism, accident and anticipation merge.

Cartier-Bresson worked with a Leica rangefinder, small and unobtrusive. He didn't direct or stage, he watched, anticipated, captured. Photography as hunting, camera as weapon (his term), photographer as witness to life's spontaneous choreography.

The image influenced generations of street photographers: be invisible, anticipate moments, trust geometry, capture life unawares. It argues photography's greatest power isn't documentation but revelation, showing us pattern, grace, and meaning in ordinary moments we'd otherwise miss.

62. W. Eugene Smith - "Tomoko Uemura in Her Bath" (1971)

.jpg?mode=max)

Location: Minamata, Japan

Medium: Photograph

A mother bathes her severely deformed daughter, victim of industrial mercury poisoning in Minamata. The composition echoes Michelangelo's Pietà, maternal love amid corporate negligence.

The family later requested the image not be reproduced (too intrusive), but it had already become environmental movement's icon.

Between 1932-1968, Chisso Corporation dumped mercury into Minamata Bay. The methylmercury accumulated in fish; residents ate poisoned fish; thousands suffered neurological damage, birth defects, death. The company denied responsibility for decades.

W. Eugene Smith, legendary photojournalist, went to Minamata (1971) to document the disaster. He photographed Tomoko Uemura, 15, with severe mercury poisoning, blind, unable to speak or walk, body contorted. Her mother bathes her with tenderness despite the girl's twisted limbs.

The composition consciously references Michelangelo's Pietà: mother cradling damaged child, love transcending suffering, beauty emerging from tragedy. Smith meant it as tribute and advocacy, making invisible victims visible, corporate crime undeniable.

The photograph appeared in Life magazine and circulated globally. It became environmental movement's icon, proving pollution has faces, that statistics conceal human cost. Chisso was eventually held responsible, paying compensation (never adequate).

But there's complexity: Tomoko's father later requested the image be withdrawn from publication. It had circulated for decades without family consent; they felt exploited, their daughter's suffering commodified. Smith photographed to advocate, but did he have right to display Tomoko's vulnerability globally?

This tension defines documentary photography: images that reveal injustice require showing suffering; yet showing suffering can exploit its victims. Good intentions don't resolve this, they expose photography's fundamental ethical problems. The image helped win compensation while violating family's privacy. Both are true.

63. Nick Út - "The Terror of War" (Napalm Girl) (June 8, 1972)

Location: Trang Bang, Vietnam

Medium: Photograph

Nine-year-old Phan Thị Kim Phúc runs naked down a road, skin burned by napalm, screaming. Other children flee; soldiers walk casually behind.

Út took her to a hospital, saving her life. The image turned American opinion against the Vietnam War. She survived, became a UNESCO ambassador, forgave.

June 8, 1972: South Vietnamese aircraft mistakenly dropped napalm on Trang Bang village. Nick Út, Associated Press photographer, was nearby covering combat. He heard explosions, saw civilians fleeing, photographed them emerging through smoke.

Kim Phúc (center) had ripped off her burning clothes, skin peeling from napalm. Út photographed her screaming in agony, then stopped photographing and drove her to hospital. His cameras saved her twice: the photograph mobilized outrage; his van transported her to medical care.

The image shocked Americans. Napalm was chemical horror: gasoline gel that stuck to skin, burning at 1,200°F. The U.S. military claimed they only used it against combatants. This photograph proved otherwise, children fleeing, skin burned, civilians in agony.

Television networks initially refused to broadcast it (child nudity), but AP argued newsworthiness prevailed. The image won the Pulitzer Prize, appeared on every front page. It crystallized opposition to the war: what are we doing? Why are we burning children?

Kim Phúc survived 17 operations, years of pain. She defected to Canada (1992), became UNESCO goodwill ambassador, met and forgave the pilot who ordered the napalm strike. Her choice demonstrates moral courage: victim becoming advocate, surviving trauma to insist on peace.

The photograph saved her and many others, by turning opinion against the war, it arguably shortened the conflict, saving lives. This is documentary photography's highest aspiration: image that doesn't just witness but intervenes, that transforms consciousness and thereby changes history.

64. Eddie Adams - "Saigon Execution" (February 1, 1968)

Location: Saigon, Vietnam

Medium: Photograph

South Vietnamese General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan executes Viet Cong prisoner Nguyễn Văn Lém with a pistol to the temple,

Adams won the Pulitzer Prize but later regretted the photo, saying it destroyed Loan's reputation without context. "Two people died in that photograph," Adams said.

February 1, 1968, during the Tet Offensive: Eddie Adams was following General Loan, South Vietnam's national police chief, through Saigon streets. Loan captured Viet Cong officer Nguyễn Văn Lém, who had allegedly killed South Vietnamese police officers and their families.

Without hesitation, Loan drew his pistol and shot Lém in the head. Adams photographed the instant the trigger pulled, Lém's face contorting, death imminent. The prisoner had no trial, no defense, no due process, just summary execution in the street.

The photograph shocked the world. It seemed to show South Vietnamese brutality, undermining American claims that we fought for democracy and freedom. How could we support a regime that executed prisoners on camera?

But Adams came to regret the photograph's impact. General Loan was defending his country against insurgents who had killed his men's families. The execution was brutal but arguably defensible by war's logic. The photograph made Loan an international villain, destroying his reputation while the wider context, Viet Cong atrocities that day, remained unknown.

Adams said later: "The general killed the Viet Cong; I killed the general with my camera. Still photographs are the most powerful weapon in the world." When Loan died (1998), Adams praised him: "He was a hero. America should be crying."

This reveals photography's power and danger: images create understanding while obscuring context. The photograph is technically perfect, ethically complex, historically devastating. It turned American opinion while possibly distorting reality. Truth and impact don't always align.

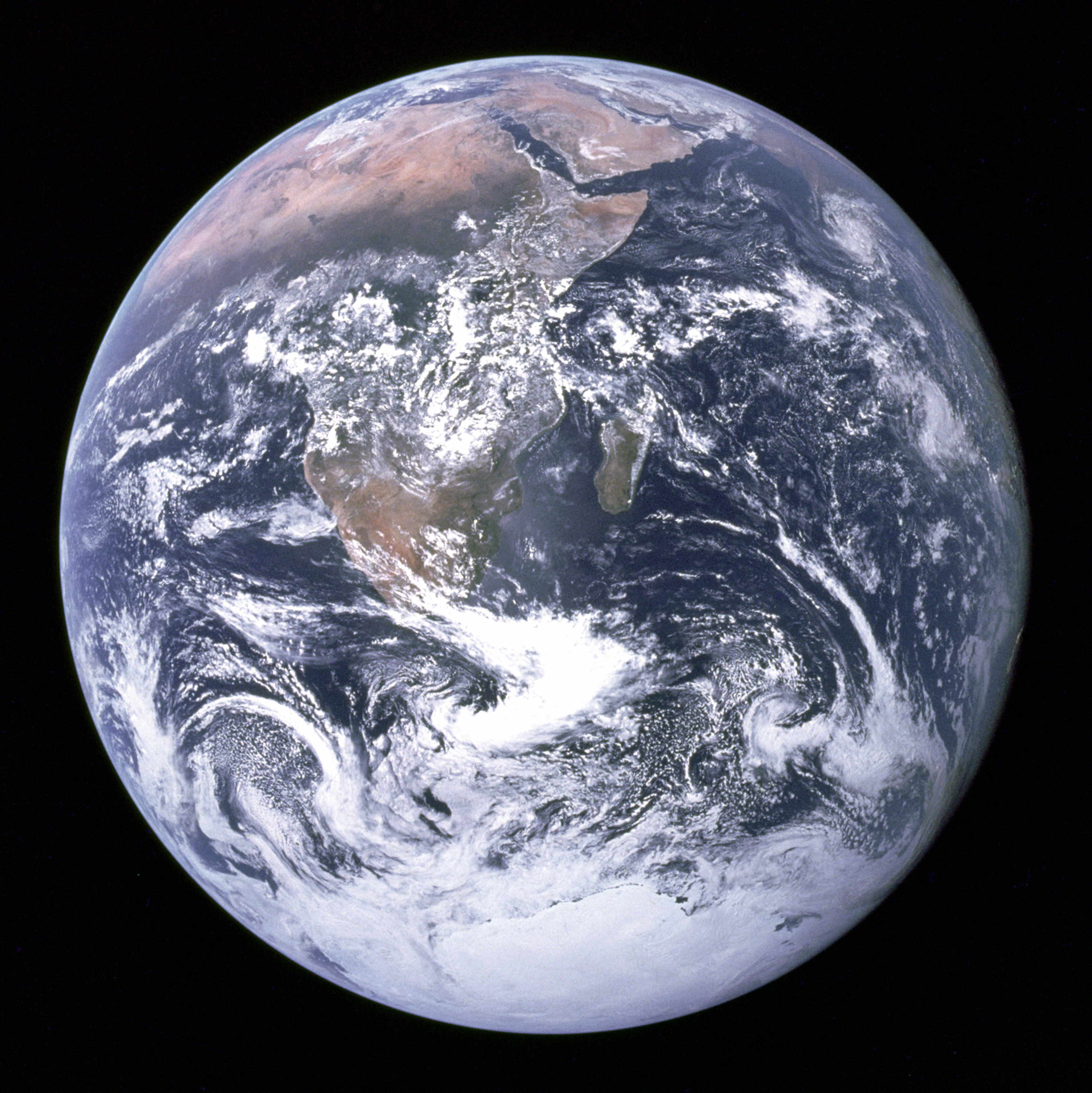

65. Earthrise (December 24, 1968)

Location: Lunar orbit

Medium: Color photograph (70mm Hasselblad)

Earth rises above the lunar horizon, a blue-and-white marble floating in black void. The first photograph showing Earth from space, it triggered environmental consciousness.

Galen Rowell called it "the most influential environmental photograph ever taken." We saw our planet as finite, fragile, borderless.

Apollo 8 was humanity's first mission to lunar orbit. On Christmas Eve 1968, astronaut William Anders looked out and saw Earth rising over the Moon's horizon. He grabbed a Hasselblad camera, loaded color film, and photographed humanity's home floating in cosmic darkness.

The image transformed consciousness. For the first time, humans saw Earth whole, not as map or globe but as actual sphere floating in void. No borders visible. No nations. Just one fragile planet suspended in infinite darkness, life's only known harbor in a lifeless universe.

The photograph triggered modern environmental movement. Suddenly, "spaceship Earth" wasn't metaphor, it was visible reality. The planet is finite; resources are limited; we're all passengers together. The image appeared on the first Earth Day (1970) and has illustrated environmental advocacy ever since.

Poet Archibald MacLeish wrote: "To see the Earth as it truly is, small and blue and beautiful in that eternal silence where it floats, is to see ourselves as riders on the Earth together, brothers on that bright loveliness in the eternal cold."

The astronauts went to explore the Moon but discovered Earth. They traveled 240,000 miles to photograph home. The image is testimony: this is all we have. There is no backup planet. The borders and conflicts that dominate politics are invisible from space, only the whole matters, the shared fragility, the collective fate.

66. The Blue Marble (December 7, 1972)

Location: En route to Moon

Medium: Color photograph (70mm Hasselblad)

The entire Earth visible, Africa, Antarctica, cloud swirls. The most reproduced image in history (competing with Che), it's become so ubiquitous we forget its radicalism.

Before 1972, no human had seen Earth whole. This image created planetary consciousness.

Apollo 17 crew photographed Earth from 18,000 miles away, far enough to see the entire illuminated hemisphere. Africa dominates, Madagascar visible, Antarctica's white mass below. Swirling clouds reveal weather systems, proving Earth is dynamic, not static. The planet looks simultaneously robust and delicate, massive yet isolated in cosmic darkness.

NASA released the photograph publicly, and it became instantly iconic. Environmental organizations adopted it, educators used it, media reproduced it endlessly. "Blue Marble" became Earth's official portrait, how we see ourselves from outside.

The image's ubiquity is both triumph and problem. It's everywhere, logos, posters, computer screens, to the point of invisibility. We've forgotten how revolutionary it was. Before 1972, Earth as whole was abstraction. After, it was photograph, fact, shared reality.

The image also reveals power dynamics: this is Earth as seen from American space program, during American mission, with American astronauts. The photograph represents technological triumph while claiming to show universal truth. Yet the image transcends nationalism, no one looks at Blue Marble and thinks "American Earth." The planet belongs to everyone and no one.

Contemporary environmental crises give the image new urgency. That swirling blue marble is warming, oceans rising, species dying. The image becomes witness to before, showing what Earth looked like when we still had time to prevent catastrophe. Future generations may view Blue Marble the way we view extinct species photographs: evidence of beauty we destroyed.

CONTEMPORARY UPHEAVALS: When Images Became Viral (1980-Present)

67. Steve McCurry - "Afghan Girl" (December 1984)

Location: Nasir Bagh refugee camp, Pakistan

Medium: Color photograph (appeared on National Geographic cover, June 1985)

Sharbat Gula, a 12-year-old Afghan refugee, stares at the camera with penetrating green eyes, fear, defiance, resilience compressed into one gaze.

Her identity remained unknown for 17 years until McCurry found her again (2002). The photograph became the refugee crisis's face.

Steve McCurry was photographing Afghan refugees in Pakistan camps (1984) when a teacher led him to a tent school for girls. He noticed one girl, piercing green eyes, red shawl, intense expression, and asked to photograph her. She agreed reluctantly, stared directly into the lens, and he captured three frames.

Her eyes contain multitudes: trauma (Soviet invasion forced her family to flee Afghanistan), fear (of photographer, of situation, of future), defiance (she will not look away), and something ineffable, dignity intact despite suffering.

The photograph appeared on National Geographic's June 1985 cover and became one of the most recognized images globally. Yet no one knew her name. She was “Afghan Girl”, anonymous symbol of refugee suffering, her individuality erased by iconicity.

McCurry searched for her for years. In 2002, after Taliban fell, he returned to Afghanistan with forensic team, showing the photograph in Pashtun regions. Eventually they found her: Sharbat Gula, married, mother of three, still living in poverty, still traumatized by decades of war.

She was surprised her photograph had become famous. She'd never seen it, lived without electricity, without media access, unaware she was one of the world's most recognizable faces. McCurry's team confirmed identity through iris recognition (eye patterns are unique, persist across decades).

The reunion was bittersweet: she gained recognition but no material benefit; her face sold millions of magazines while she remained poor. National Geographic established a fund for her education and support, but fundamental questions remain: Who owns refugee stories? Who benefits from photographing suffering? Did the world's attention help her or exploit her?

68. Jeff Widener - "Tank Man" (June 5, 1989)

Location: Tiananmen Square, Beijing

Medium: Photograph

An anonymous man stands before a column of tanks the day after the Tiananmen Square massacre, shopping bags in hand, refusing to move. The lead tank tries to go around him; he steps back in front.

His identity remains unknown (probably executed). The image became democracy's icon, individual defiance against totalitarian power. China censors it; the world remembers.

June 5, 1989, one day after Chinese military killed hundreds (possibly thousands) of protesters in Tiananmen Square: Jeff Widener, Associated Press photographer, was in Beijing shooting from his hotel balcony with telephoto lens. A column of tanks approached; a solitary man walked into their path.

For several minutes, man and tanks faced each other. The tanks tried going around; the man sidestepped to block them. Eventually, the lead tank stopped. The man climbed onto it, apparently speaking to the crew. Then other civilians pulled him away into the crowd.

Who was he? What happened to him? Speculation ranges from execution to life in hiding to escape abroad. China has never confirmed identity or fate. This anonymity makes him universal, every individual facing tyranny, Everyman refusing to accept injustice.

Four photographers captured similar images from different hotels; Widener's became most famous. The composition is perfect: single figure in white shirt, shopping bags in hands (ordinary man, not activist), facing military machinery. David versus Goliath, individual versus state, humanity versus power.

China censors the image, it's blocked online, omitted from textbooks, forbidden in media. Yet it circulates globally as symbol of Chinese government's brutality and individual courage. Younger Chinese generations often don't recognize it, testimony to censorship's effectiveness. Older Chinese who lived through it carry the image in memory, even if they can't see it online.

The photograph asks: What is courage? Standing before tanks with no weapons except refusal, no protection except conviction, no hope except bearing witness. The man expected to die, his defiance was farewell performance, final testimony. That he might have survived changes nothing; his stance remains exemplary.

69. Kevin Carter - "The Vulture and the Little Girl" (March 1993)

Location: Ayod, Sudan

Medium: Photograph

A starving Sudanese child collapses on her way to a feeding center while a vulture waits nearby. Carter won the Pulitzer Prize, then was vilified for not helping.

Traumatized by criticism and by witnessing atrocities, he committed suicide three months after winning the Pulitzer.

Kevin Carter was covering Sudan's famine (1993) when he encountered this scene: a child collapsed from starvation, vulture perched nearby. He photographed it, waited 20 minutes hoping the bird would spread its wings (better composition), then chased it away. He said the child resumed crawling toward the feeding center.

The photograph went viral, appearing globally, winning the Pulitzer Prize. Then backlash: Why didn't he help? Why did he prioritize photographing over intervening? Is journalism's objectivity an excuse for complicity?

Carter defended himself, feeding stations had rules against physical contact (disease prevention); he couldn't know every child's story; his job was documenting crisis to mobilize help. But criticism intensified. He received hate mail. At Pulitzer ceremony, people asked about the child rather than congratulating him.

Carter was already traumatized from years covering violence, South African apartheid struggles, Mozambican civil war, Sudanese famine. He'd witnessed torture, execution, mass starvation. The criticism over this photograph broke him. Three months after the Pulitzer, he committed suicide, his note citing "the vivid memories of killings and corpses and anger and pain."

The photograph raises impossible questions: What is photographer's responsibility to subjects versus public? If Carter had helped this child but not photographed the scene, would more children have died from lack of awareness? Do photographers violate human dignity by documenting suffering, or do they honor it by making invisible victims visible?

There's no resolution. Documentary photographers navigate impossible ethics, required to witness without interfering, to photograph suffering without exploitation, to maintain objectivity while remaining human. Carter couldn't sustain that contradiction.

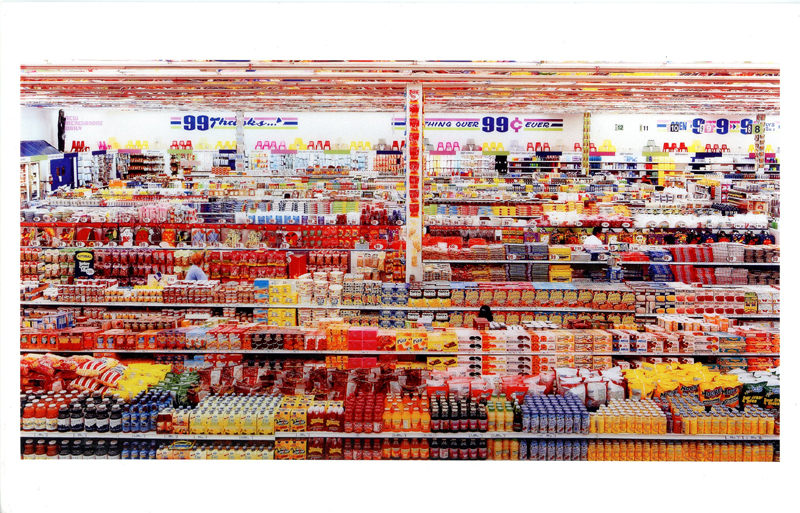

70. Andreas Gursky - "99 Cent II Diptychon" (2001)

Location: Photographed in Los Angeles; digitally composed

Medium: C-print photograph (207 × 337 cm)

An endless 99-cent store shelf, products multiplied through digital manipulation into infinity. Sold for $3.34 million (2007), it was briefly the most expensive photograph ever sold.

The irony is intentional: cheap consumer goods immortalized as high art.

Andreas Gursky photographs architectural spaces and landscapes at monumental scale, then digitally manipulates them to heighten their effects. 99 Cent II shows a Los Angeles discount store's shelves, but Gursky has removed visual interruptions, multiplied sections, creating overwhelming abundance.

The image is simultaneously seductive and horrifying: so many products, so many choices, capitalism's promise of infinite options. Yet it's also dystopian, this abundance is trash, these choices meaningless, consumption replacing meaning. The colors are garish; the repetition numbing.

That this photograph, showing cheap products sold for 99 cents, itself sold for $3.34 million is profound irony. Gursky makes explicit what's usually implicit: art is commodity like any other product. The museum and the discount store operate on same logic, value assigned through presentation, meaning created through context.

Gursky's work represents photography's transformation: no longer "capturing reality" but constructing it. Digital manipulation allows photographers to create images that never existed, assembling reality from fragments. Is this still photography? Does it matter? The boundaries between photography, painting, and digital art have dissolved.

The photograph also documents globalization: these products come from dozens of countries, assembled in California, sold cheap through economies of scale. The 99-cent store is capitalism's endgame, goods so abundant they're nearly worthless. Gursky's image is monument to this system, simultaneously celebrating and critiquing it.

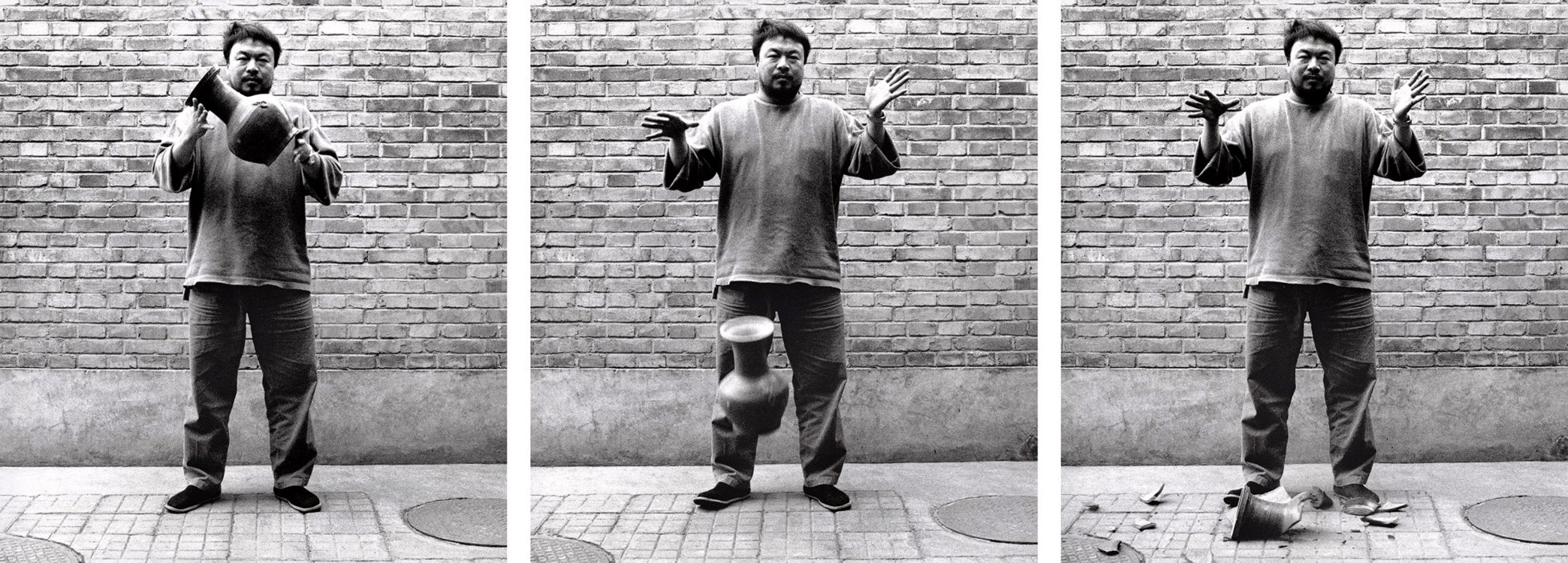

71. Ai Weiwei - "Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn" (1995)

Location: Beijing studio

Medium: Triptych of black-and-white photographs

Three photographs show Ai Weiwei holding a 2,000-year-old Han Dynasty urn, releasing it, and the instant before it shatters. Iconoclasm as art, destroying heritage to question value, authority, preservation.

Chinese authorities were horrified; conceptual artists celebrated.

Ai Weiwei, China's most famous dissident artist, purchased a 2,000-year-old Han Dynasty urn (208 BCE-220 CE), photographed himself dropping it, and exhibited the triptych. The gesture is multiple provocations simultaneously: destroying cultural heritage, questioning museum value systems, challenging authority's control over history, demonstrating art as idea rather than object.

The urn's destruction is irreversible, no conceptual work, no artistic statement can restore 2,000 years of history. Yet Ai argues the photographs preserve the urn more effectively than museum storage. The urn's destruction creates images that circulate globally, ensuring millions know it existed. Is this preservation or vandalism?

The work questions: What gives objects value? Age? Rarity? Official designation? Or meaning created through context? The urn was valuable because authorities said it was. Ai destroys their authority by destroying their valued object. In China, where Communist Party controls cultural narratives, this gesture is political dynamite.

Chinese authorities considered prosecuting Ai for destroying cultural artifacts. That they didn't (he was already internationally famous) demonstrates state's ambivalence: they want to suppress dissent while maintaining appearance of cultural sophistication. Ai exploits this contradiction, making art that forces authorities to choose between appearing totalitarian or tolerating criticism.

The triptych format references Christian altarpiece, holding, releasing, destroyed. It's secular crucifixion: the old order must die for the new to emerge. Ai performed this gesture multiple times with different ancient urns, each destruction documented photographically, each destroyed object becoming immortal through documentation.

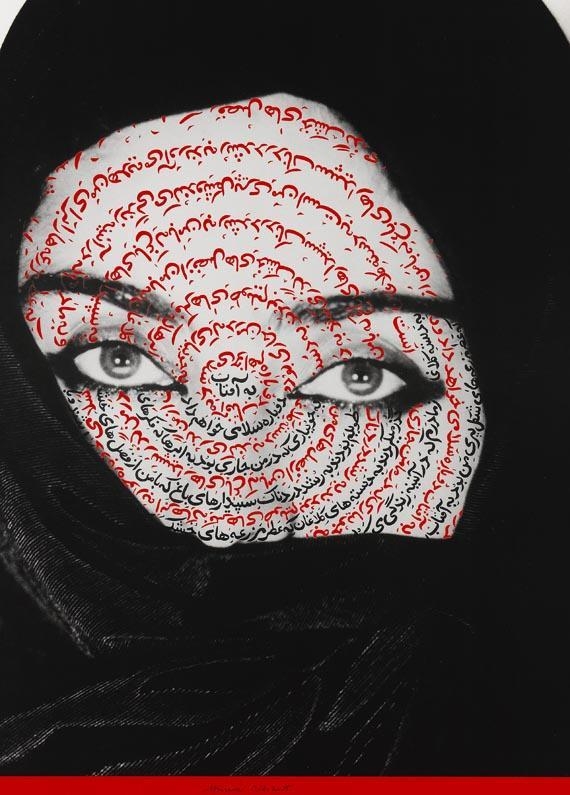

72. Shirin Neshat - "I Am Its Secret" (1993)

Location: Studio photograph

Medium: Gelatin silver print with ink

A woman's face, partially veiled, eyes fierce, Farsi calligraphy inscribed on exposed skin. Neshat's series explores Iranian women's complex relationship with Islam post-Revolution, neither victims nor willing participants, but agents navigating oppression.

Shirin Neshat, Iranian-American artist, created her "Women of Allah" series (1993-1997) exploring post-revolutionary Iranian women's identities. She photographs women (often herself) wearing chadors, holding weapons, with Farsi text written on exposed skin, hands, faces, feet.

The text is usually Persian poetry, Forough Farrokhzad's feminist verses, mystical Sufi writings, creating counterpoint to images' militancy. The women aren't simply victims of patriarchal oppression or willing Islamic warriors. They're complex subjects navigating impossible contradictions: religious faith and feminist identity, cultural tradition and personal autonomy, submission and resistance.

Western media often depicts Muslim women as passive victims needing rescue. Neshat refuses this simplification. Her subjects gaze directly at camera with fierce intelligence, holding weapons not as threats but as complicated symbols, armed yet vulnerable, militant yet spiritual, covered yet exposed.

The calligraphy written on skin is crucial: in Islamic tradition, the body is private, protected from public gaze. Writing poetry on faces and hands makes private public, transforms body into text, literalizes the idea that women's identities are written on their bodies by culture, religion, family, state.

Neshat hasn't been able to return to Iran since 1996, the work is too controversial, too critical of the Islamic Republic. She makes art about Iran from exile, her perspective simultaneously insider (Iranian-born, culturally grounded) and outsider (American-based, internationally famous). This double perspective gives the work its power: she understands both worlds and refuses to simplify either.

73. Anonymous - "9/11 - World Trade Center Towers Burning" (September 11, 2001)

Location: New York City

Medium: Photograph

The Twin Towers burn, smoke billowing against blue sky. This image. captured by thousands of cameras simultaneously, became the 21st century's defining trauma.

Every angle, every perspective documented. The most photographed atrocity in history, it divided time into before and after.

September 11, 2001, 8:46 AM: American Airlines Flight 11 crashed into World Trade Center North Tower. Eighteen minutes later, United Airlines Flight 175 hit the South Tower. Thousands of cameras, professional, amateur, surveillance, captured every moment.

The images circulated instantly: television broadcast live, photographs appeared online within minutes, videos uploaded to nascent social media. For the first time, global catastrophe was documented in real-time from thousands of perspectives. The 21st century's first major trauma was also its most visually recorded.

The towers burning against clear blue sky created surreal beauty, apocalypse on perfect autumn morning. Smoke billowing black against blue, flames visible through windows, tiny figures visible at upper floors waving for help. The images were simultaneously aesthetic and horrifying, sublime disaster playing on endless loop.

Television networks replayed impacts hundreds of times, burning the image into collective memory. The towers' collapse, first South Tower at 9:59 AM, then North at 10:28 AM, was broadcast live to billions. Humanity watched in real-time as 3,000 people died, as architecture failed, as ash cloud enveloped Manhattan.

The images galvanized American response, justifying Afghanistan invasion, Iraq War, War on Terror, surveillance expansion, civil liberties restrictions. These photographs didn't just document history; they created political consent for actions that followed. Images mobilized nation toward wars that killed hundreds of thousands.

Yet there's no single iconic 9/11 photograph, rather, thousands of images that collectively construct memory. This is 21st-century visual culture: not one authoritative image but proliferating perspectives, multiple truths, endless circulation.

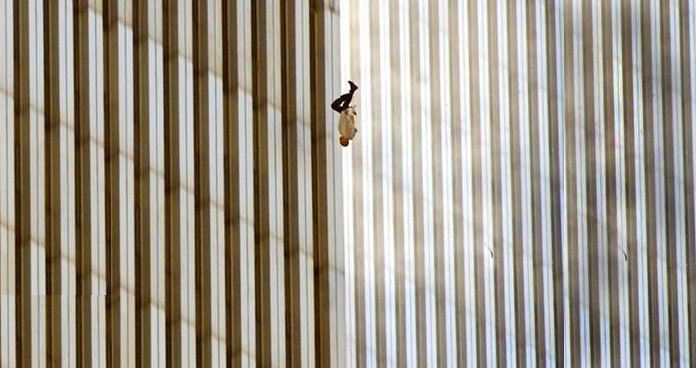

74. Richard Drew - "The Falling Man" (September 11, 2001, 9:41:15 a.m.)

Location: World Trade Center, New York

Medium: Photograph (sequence)

A man falls headfirst from the North Tower, body vertical, eerily composed against the building's lines. An estimated 200 people jumped; Drew photographed one's descent.

American media barely published it (too disturbing). His identity remains officially unknown (probably Jonathan Briley). The image is 9/11's most suppressed.

At 9:41 AM, Richard Drew photographed a man falling from World Trade Center's North Tower. The photograph shows him perfectly vertical, headfirst, arms at sides, falling past the building's aluminum cladding. The composition is almost peaceful, he appears to dive rather than fall, body controlled rather than flailing.

The image ran on September 12 in several newspapers, then was immediately suppressed. Readers complained it was too disturbing, too graphic, disrespectful to victims and families. Newspapers withdrew it. Television never showed the jumpers. Official death count categorizes them as "died in the attacks," not as jumpers, erasing their agency, their final choice.

Yet an estimated 200 people jumped. They faced impossible choice: burn alive or jump. They chose. Their fall took approximately 10 seconds from 100th floor. Some held hands. Some jumped together. Some removed clothing because it was burning. Drew photographed one man's final seconds.

Journalists spent years trying to identify him. The most likely candidate: Jonathan Briley, 43, audio technician at Windows on the World restaurant. His family has never confirmed, some families don't want to know, preferring uncertainty to accepting their loved one jumped.

The photograph was suppressed because it forced confrontation with victims' agency. If they jumped, they chose death over burning. This complicates the narrative, they weren't just killed by terrorists; they exercised final autonomy over intolerable circumstance. Americans wanted victims as passive martyrs, not active participants in their own deaths.

The image remains controversial. Some consider it essential testimony, these people existed, made impossible choices, deserve remembrance. Others consider it exploitation, publishing without family consent, aestheticizing suffering, making entertainment from trauma. Both perspectives have merit; neither resolves the contradiction.

75. Abu Ghraib Photographs - "Hooded Man on Box" (Late 2003)

Location: Abu Ghraib prison, Iraq

Medium: Digital photograph

A hooded prisoner stands on a box, arms extended, wires attached (told he'd be electrocuted if he fell). The pose evokes both crucifixion and the Statue of Liberty, America's ideals mocked through torture.

The Abu Ghraib photos destroyed US moral authority in Iraq War.

In 2004, CBS News and The New Yorker published photographs from Abu Ghraib prison showing US soldiers torturing Iraqi detainees. The images were horrific: naked prisoners piled in pyramids, dogs threatening detainees, sexual humiliation, beatings, a corpse packed in ice. Soldiers smiled, gave thumbs up, torture as entertainment.

The "Hooded Man on Box" became the series' iconic image. The hooded figure's outstretched arms consciously or unconsciously echo Christian crucifixion imagery. But the wires (fake, he wasn't actually connected to electricity, though he believed he was) suggest technological torture. The hood dehumanizes him, he has no face, no identity, just terrorized body.

The pose also resembles the Statue of Liberty, arms outstretched, standing elevated. This resemblance makes the image devastatingly ironic: America invaded Iraq ostensibly to bring democracy and freedom, instead delivering torture and abuse. The photograph literalizes this contradiction, Liberty as torture victim.

The photographs emerged from soldiers' own documentation, they took pictures casually, sharing them digitally, treating torture as photography opportunity. This casual violence is perhaps more disturbing than systematic torture programs. These weren't trained interrogators following protocol (however immoral), they were bored soldiers entertaining themselves with detainees' suffering.

When published, the photographs destroyed any remaining international support for Iraq War. They confirmed critics' accusations: America tortures, breaks international law, behaves as occupying force rather than liberator. Military prosecuted some soldiers, but higher-level authorization was never addressed. Low-ranking personnel were scapegoated while policies permitting abuse remained intact.

The photographs' digital nature is significant, easily copied, shared, circulated. Unlike previous wars where military controlled image dissemination, digital photography made censorship nearly impossible. Soldiers' casual documentation became evidence of war crimes, private entertainment became public testimony.

The Image Devours Reality

From Picasso's fracturing of space to the Abu Ghraib images that circulated instantly worldwide, these 25 images chronicle modernity's visual transformation. We learned that images don't just show reality, they create it, destroy it, replace it.

The 20th century began with artists questioning representation itself: What happens when we refuse realistic depiction? Cubism, abstraction, and conceptual art answered: art becomes idea, gesture, question rather than window onto world. Duchamp's urinal proved context creates meaning; Malevich's black square demonstrated painting's essence is mark-making itself.

Then photography forced reconciliation: if cameras record reality mechanically, what's painting's purpose? Instead of killing painting, photography liberated it, artists could explore abstraction precisely because cameras handled documentation.

But photography proved equally complex. Images that seemed objective were manipulated, staged, composed. Documentary photographers witnessed suffering while photographing it, creating ethical dilemmas without resolution. War photography oscillated between testimony and exploitation, between mobilizing outrage and aestheticizing violence.

The century's middle decades brought unprecedented horror: Holocaust, Hiroshima, Vietnam. Images documented atrocities, providing evidence while traumatizing viewers. We saw that photographs could end wars (Vietnam), justify wars (9/11), and become evidence of war crimes (Abu Ghraib).

Then space travel provided ultimate perspective shift: seeing Earth from outside created planetary consciousness. We recognized our collective vulnerability, one fragile planet in cosmic darkness, no backup, no escape. These images triggered environmental movement, proving that seeing differently enables thinking differently.

By century's end, digitization changed everything. Images became infinitely reproducible, endlessly manipulable, instantly distributable. The photograph lost its privileged relationship to truth. Digital manipulation meant every image was potentially fake; yet proliferation meant every moment was potentially documented.

We now inhabit visual landscape unimaginable to previous generations: billions of images created daily, circulating instantly, shaping consciousness faster than thought. The image has become reality's dominant mode, we experience through screens, remember through photographs, construct identities through image curation.

These 25 images prepared us for this transformation. They taught us representation is construct, documentation is interpretation, seeing is believing only when we choose to believe.

In our final installment, we'll explore the 21st century's first decades: social media's image explosion, artificial intelligence generating indistinguishable fakes, virtual realities replacing physical experience, and the ultimate question, what happens when images become more real than reality itself?

The eternal gaze continues, but now it gazes back, surveillance cameras, facial recognition, algorithmic curation. We've created visual systems that see us more completely than we see ourselves.

Next: The Digital Convergence - Images 76-100

Share this

Dinis Guarda

Author

Dinis Guarda is an author, entrepreneur, founder CEO of ztudium, Businessabc, citiesabc.com and Wisdomia.ai. Dinis is an AI leader, researcher and creator who has been building proprietary solutions based on technologies like digital twins, 3D, spatial computing, AR/VR/MR. Dinis is also an author of multiple books, including "4IR AI Blockchain Fintech IoT Reinventing a Nation" and others. Dinis has been collaborating with the likes of UN / UNITAR, UNESCO, European Space Agency, IBM, Siemens, Mastercard, and governments like USAID, and Malaysia Government to mention a few. He has been a guest lecturer at business schools such as Copenhagen Business School. Dinis is ranked as one of the most influential people and thought leaders in Thinkers360 / Rise Global’s The Artificial Intelligence Power 100, Top 10 Thought leaders in AI, smart cities, metaverse, blockchain, fintech.

More Articles

Renaissance Humanism and the Birth of the Modern Gaze: Images That Taught Us to See Ourselves

When Vision Becomes Destiny: The First 25 Images That Shaped Human Consciousness

What a Small Indian Village Teaches the World About Sustainability

Community as Classroom: When the Village Teaches : Redefining Where Learning Happens