What Carl Jung Meant by Individuation and Why It Still Matters

Sara Srifi

Tue Nov 04 2025

What does it mean to become your true self? Explore Jung's powerful concept of individuation, shadow work, and authentic living—a guide that's more relevant than ever.

In an age of selfies, personal brands, and constant self-optimisation, we're more focused on the "self" than ever before. Yet paradoxically, many people report feeling lost, fragmented, or disconnected from who they truly are. Over a century ago, Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung identified this core human struggle and offered a powerful framework for understanding it: individuation.

But what exactly did Jung mean by this term? And why does a concept from early 20th-century psychology still resonate so deeply in our modern world?

Understanding Jung's Concept of Individuation

At its essence, individuation is the lifelong process of becoming your true, authentic self, not the self your parents wanted you to be, not the persona you present to the world, but the whole, integrated person you're meant to become.

Jung didn't see individuation as self-improvement or ego inflation. Rather, he viewed it as a profound psychological journey toward wholeness, where you integrate all aspects of your personality, including the parts you'd rather ignore or deny.

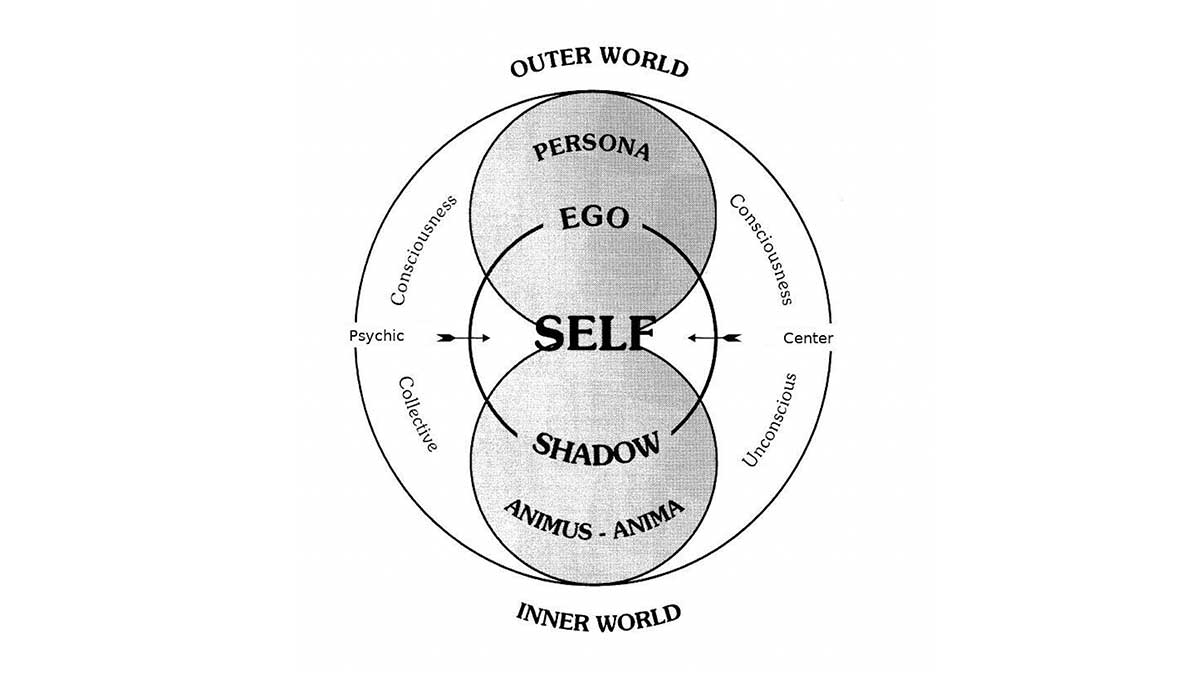

The Architecture of the Psyche

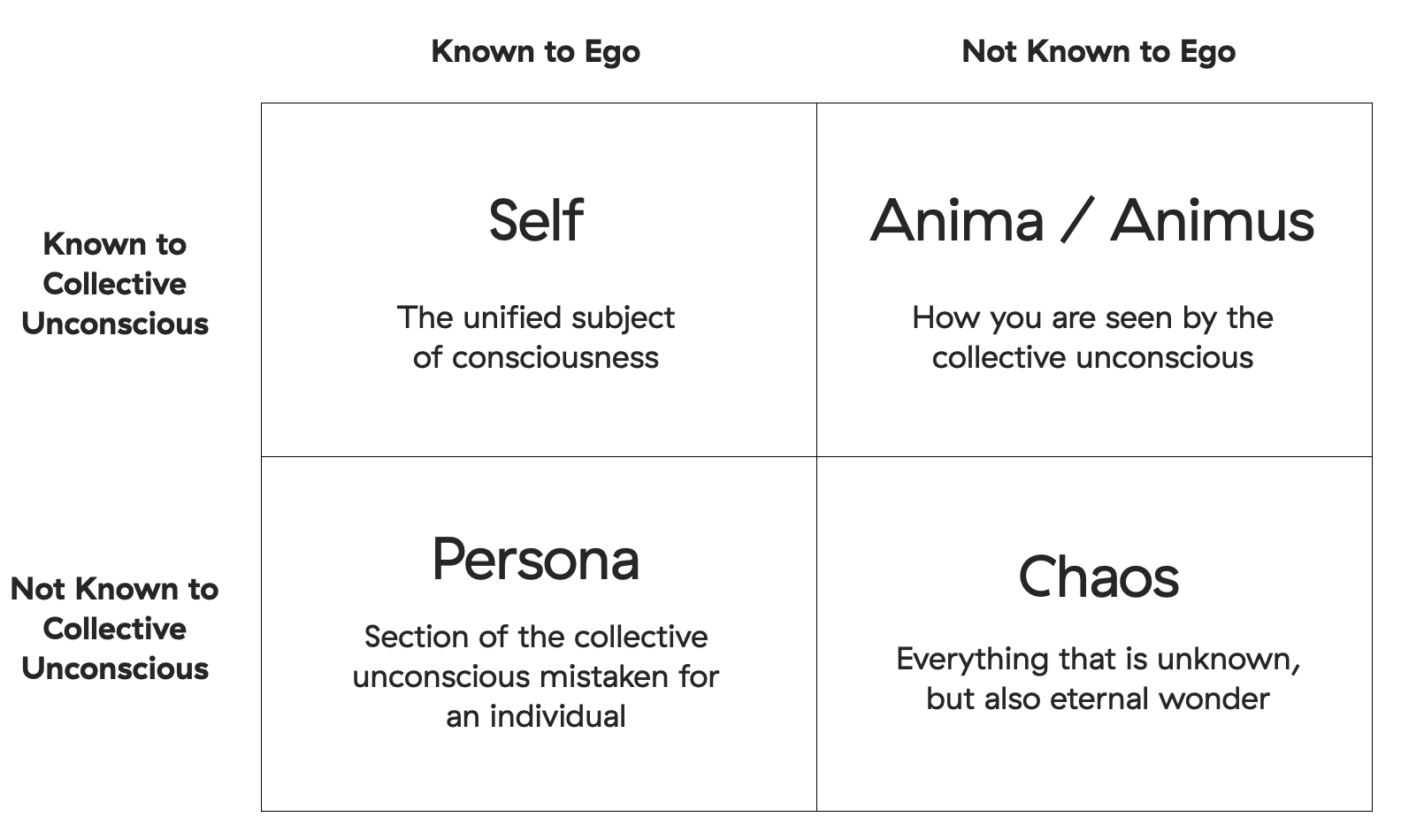

To grasp individuation, you need to understand Jung's map of the human psyche. He proposed that our personality consists of several key components:

- The Ego is your conscious mind, the "you" that you identify with in everyday life. It's the part that makes decisions, forms opinions, and navigates daily reality.

- The Persona is the social mask you wear, the version of yourself you present to the world. It's your professional demeanor, your social roles, the carefully curated image you project. The persona isn't inherently false, but it's incomplete, a necessary adaptation to social expectations rather than your full truth.

- The Shadow contains everything you've rejected, repressed, or denied about yourself. These are the qualities you consider unacceptable, your anger, jealousy, selfishness, or desires that contradict your self-image. The shadow isn't purely negative; it also contains unrealized potential and creative energy you've suppressed.

- The Anima and Animus represent the contrasexual aspects of your psyche, the feminine qualities in men (anima) and masculine qualities in women (animus). These archetypes influence how you relate to others and connect with aspects of yourself that complement your conscious gender identity.

- The Self (with a capital S) is the totality of your being, conscious and unconscious, ego and shadow, masculine and feminine all integrated. The Self represents psychological wholeness, the ultimate goal of individuation.

The Journey of Individuation: How It Unfolds

Individuation isn't a linear process with clear checkpoints. Jung saw it as a spiraling journey that typically intensifies during midlife, though it can begin at any age.

Confronting the Shadow

The first major challenge involves facing your shadow, those rejected parts of yourself that you've pushed into the unconscious. This confrontation often happens through projection: you notice that the qualities you most despise in others are actually disowned aspects of yourself.

When you find yourself having an unusually strong emotional reaction to someone, whether it's contempt, envy, or inexplicable anger, there's often shadow material at play. The person has become a screen onto which you project your own unacknowledged traits.

Integrating the shadow doesn't mean acting on every impulse or becoming your "worst self." It means acknowledging these aspects exist, understanding their origins, and consciously deciding how to relate to them. A person who denies their capacity for anger, for example, might become passive-aggressive or suddenly explode. Someone who owns their anger can express it constructively or channel it into positive action.

Withdrawing Projections

As you become more conscious, you begin withdrawing projections, recognizing that what you see in others often says more about your internal landscape than about them. This process is humbling but liberating. You stop needing others to be villains or saviors and start relating to them as complex human beings.

Integrating the Anima and Animus

For Jung, psychological wholeness requires integrating contrasexual elements. Men must acknowledge and develop their capacity for receptivity, emotion, and intuition (anima). Women must own their assertiveness, logic, and ambition (animus).

In today's evolving understanding of gender, this concept remains relevant when understood as integrating complementary qualities within yourself, balancing action with receptivity, thinking with feeling, independence with connection.

Encountering the Self

The culmination of individuation involves what Jung called encountering the Self, experiencing a sense of wholeness that transcends the ego. This isn't a permanent state but rather moments of profound integration and meaning that reorient your life around deeper values.

Jung described this experience using various symbols across cultures: the mandala, the divine child, the philosopher's stone. These images represent psychic totality, the sense that all your disparate parts have found their rightful place in a meaningful whole.

Why Individuation Matters More Than Ever

You might wonder: why does a theory developed in the early 1900s remain relevant in our hyperconnected, rapidly changing world? The answer lies in several unique challenges of contemporary life.

The Crisis of Authenticity

Modern life offers unprecedented freedom to create your identity. You can curate your image on social media, reinvent yourself in new cities, and craft a personal brand that markets you to the world. Yet this freedom often breeds anxiety rather than fulfillment.

Many people report feeling like frauds, constantly performing for an imaginary audience. The gap between the persona you project and the person you actually are creates exhausting cognitive dissonance. Individuation offers a path through this crisis by encouraging you to know yourself deeply rather than simply managing your image.

The Fragmentation of Self

You wear different masks in different contexts: professional at work, casual with friends, dutiful with family, uninhibited online. While some adaptation is healthy, excessive fragmentation leaves you feeling like a collection of roles rather than a coherent person.

Individuation provides a framework for integration, not eliminating these different expressions, but grounding them in a unified sense of self that remains consistent across contexts.

The Shadow in the Digital Age

Social media algorithms amplify shadow projection on a massive scale. Online spaces become arenas where we project our unconscious material onto strangers, political opponents, and celebrities. The result is polarization, outrage, and dehumanization.

Understanding individuation can help you recognize when you're projecting rather than perceiving. It cultivates the self-awareness necessary for constructive dialogue in an increasingly divided world.

The Search for Meaning

Jung believed individuation wasn't just about psychological health, it was fundamentally about meaning. In a secular age where traditional religious narratives have lost their grip on many people, individuation offers a framework for encountering the sacred within your own psyche.

The journey toward wholeness provides inherent purpose: you're not just optimizing yourself for productivity or pleasure, but participating in a profound process of psychological and spiritual development.

Practical Pathways to Individuation

While individuation is lifelong and ultimately unique to each person, certain practices can support the journey.

Dream analysis was Jung's primary tool for accessing the unconscious. Your dreams speak in symbols, revealing hidden conflicts, unacknowledged desires, and creative solutions your conscious mind hasn't considered. Keeping a dream journal and reflecting on recurring images can illuminate your inner landscape.

Active imagination involves engaging with unconscious material while awake, dialoguing with inner figures, exploring fantasy images, or allowing spontaneous artistic expression. This practice helps you relate to the psyche as a living system rather than trying to control it through willpower alone.

Shadow work requires ruthless honesty about your projections. When you notice strong emotional reactions, pause and ask: "What might this be showing me about myself?" This doesn't mean all your perceptions are projection, but the question opens space for self-examination.

Creative expression provides a natural channel for unconscious material. Whether through art, music, writing, or movement, creative practices allow different aspects of yourself to emerge without the censorship of the rational mind.

Therapy and depth work offer structured support for the individuation journey. A skilled therapist, particularly one trained in Jungian or depth psychology, can help you navigate the challenges of confronting the shadow and integrating disowned parts of yourself.

Solitude and reflection create the internal space necessary for individuation. In a world of constant stimulation and connection, regular periods of solitude allow you to hear your own voice beneath the noise of others' expectations and opinions.

The Paradox of Individuation

One of Jung's most profound insights is that true individuation doesn't lead to isolation or narcissism. Paradoxically, becoming more fully yourself enables deeper connection with others.

When you've integrated your shadow, you stop projecting it onto others and can see them more clearly. When you've developed your contrasexual side, you can relate to diverse perspectives. When you've found your own center, you don't need others to complete you, which allows for genuine intimacy rather than desperate dependency.

Individuation also connects you to something larger than yourself. Jung believed the psyche has a collective dimension, that by diving deeply into your own unconscious, you encounter universal patterns and symbols that link you to all of humanity. Your journey toward wholeness is simultaneously deeply personal and profoundly collective.

The Unfinished Journey

Jung was clear that individuation is never complete. There's no final destination where you've "arrived" at perfect wholeness. Instead, it's a continuous process of becoming, a lifelong dialogue between consciousness and the unconscious.

This perspective offers relief in a culture obsessed with completion and achievement. You don't need to fix yourself or reach some idealized version of who you should be. Instead, you're invited into an ongoing relationship with the mystery of your own being.

In our fractured, disorienting times, Jung's vision of individuation offers something desperately needed: a map for the inner journey. Not a rigid formula, but a flexible framework for making sense of your struggles, integrating your contradictions, and becoming more authentically yourself.

The question Jung posed over a century ago remains urgently relevant: Will you live according to others' expectations and your own limited self-concept, or will you undertake the challenging, rewarding work of becoming who you truly are?

The invitation to individuate is an invitation to live more fully, love more deeply, and engage more authentically with the profound mystery of being human. That's why it still matters—and perhaps why it matters now more than ever.

previous

Classroom Practices That Nurture Reflection, Empathy, and Presence: A Complete Guide for Educators

next

Elder Voices of the Millennium: Cornel West

Share this

Sara Srifi

Sara is a Software Engineering and Business student with a passion for astronomy, cultural studies, and human-centered storytelling. She explores the quiet intersections between science, identity, and imagination, reflecting on how space, art, and society shape the way we understand ourselves and the world around us. Her writing draws on curiosity and lived experience to bridge disciplines and spark dialogue across cultures.