Why Is the Heart Associated with Love?

Maria Fonseca

Tue Jul 22 2025

A Journey Through Science, Soul, and Symbol

“Tell me where is fancy bred,

Or in the heart, or in the head?”

– William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice

For thousands of years, poets and lovers, scientists and saints have gazed inward and upward, wondering why—when love stirs in us—it seems to press its thumbprint on the heart. Why does a pulse quicken at the sight of a beloved? Why is the broken-hearted not just a figure of speech, but a bodily sensation, heavy and raw? And what truth lies behind the eternal metaphor of the heart as the seat of love?

To answer this, we must travel across disciplines and centuries—through the terrain of biology, the corridors of myth, and the shimmer of human longing. For the heart is more than a pump. It is a symbol, a sensor, and, perhaps, a storyteller.

The Biology of Feeling: How the Heart Responds to Love

Biologically speaking, the heart is a powerful muscle—roughly the size of a fist—whose rhythmic contractions sustain life, beating more than 100,000 times a day. But when we speak of “feeling” with the heart, we are referring to more than its circulatory role.

When a person experiences love—whether romantic, platonic, or parental—the brain floods the body with a cocktail of chemicals: dopamine, oxytocin, serotonin, adrenaline. These hormones:

- Increase heart rate

- Alter blood pressure

- Trigger flushes, tingles, and warmth

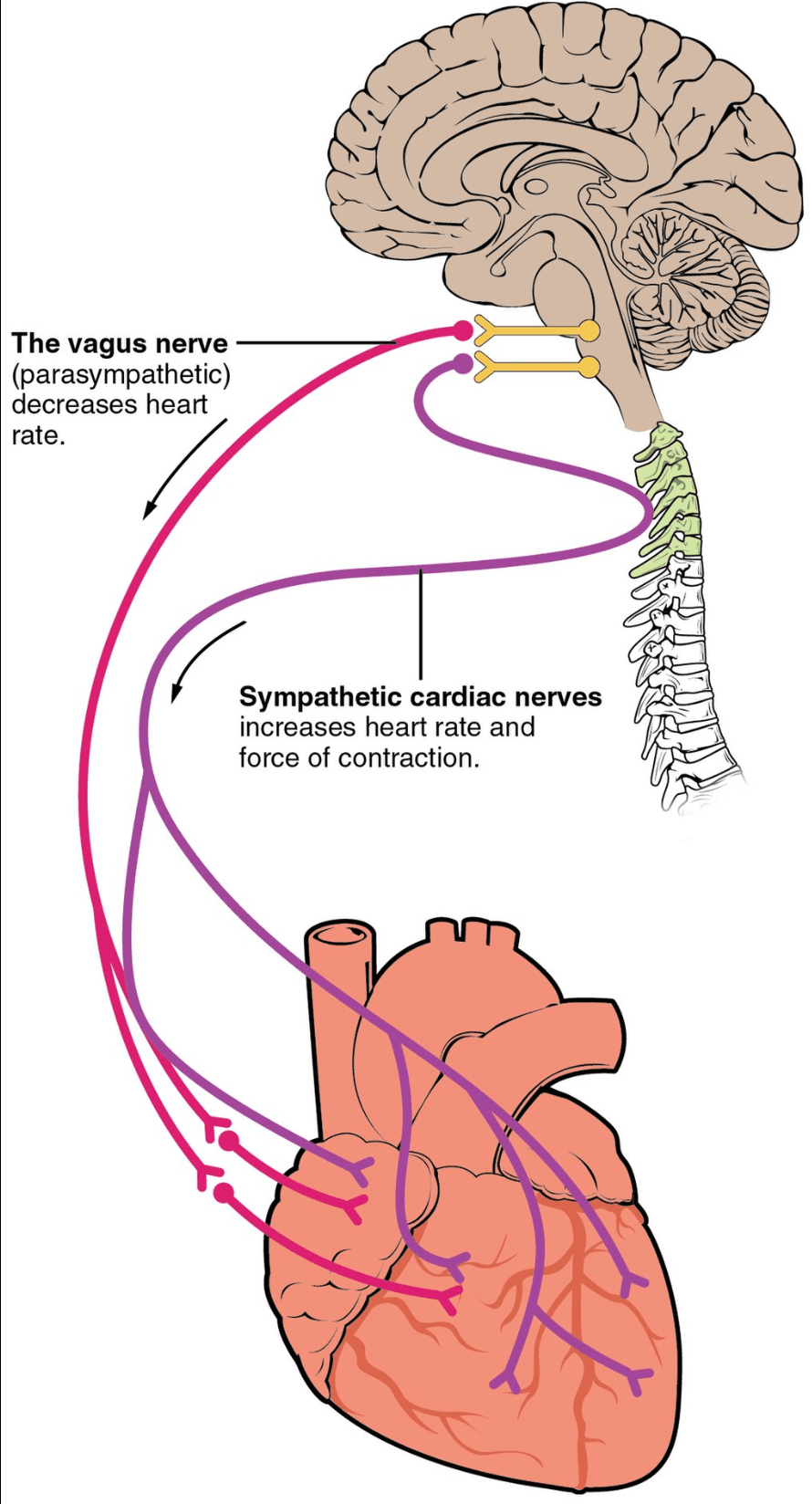

This is no illusion. When you “feel it in your chest,” you're likely experiencing measurable changes in autonomic nervous system activity—a symphony of parasympathetic and sympathetic responses that can cause the heart to flutter, race, or ache.

In moments of intense emotional arousal (joy, grief, desire), the vagus nerve, which links the heart and brain, becomes active. It helps explain why we can feel "calmly connected" in moments of love—or devastated when that love is lost.

Neuroscience and the Heart-Brain Dialogue

Modern neuroscience reveals a startling truth: the heart and brain are in constant conversation.

The heart contains approximately 40,000 neurons—a "little brain" that processes information, remembers patterns, and sends messages to the larger brain. According to the HeartMath Institute, up to 90% of the communication between heart and brain is from the heart to the brain, not the other way around.

When we experience emotions of love or appreciation, the heart’s rhythm becomes more coherent—smooth, sine-wave-like. This heart coherence influences:

- Cognitive clarity

- Emotional regulation

- Immune function

Love, then, is not only an emotion but a physiological state of harmony, one in which body and mind are synchronized in a dance of resonance.

Ancient Symbolism: A Sacred Organ Across Cultures

Before science, there was story. And in the stories of nearly every civilization, the heart was revered not only as vital but as divine.

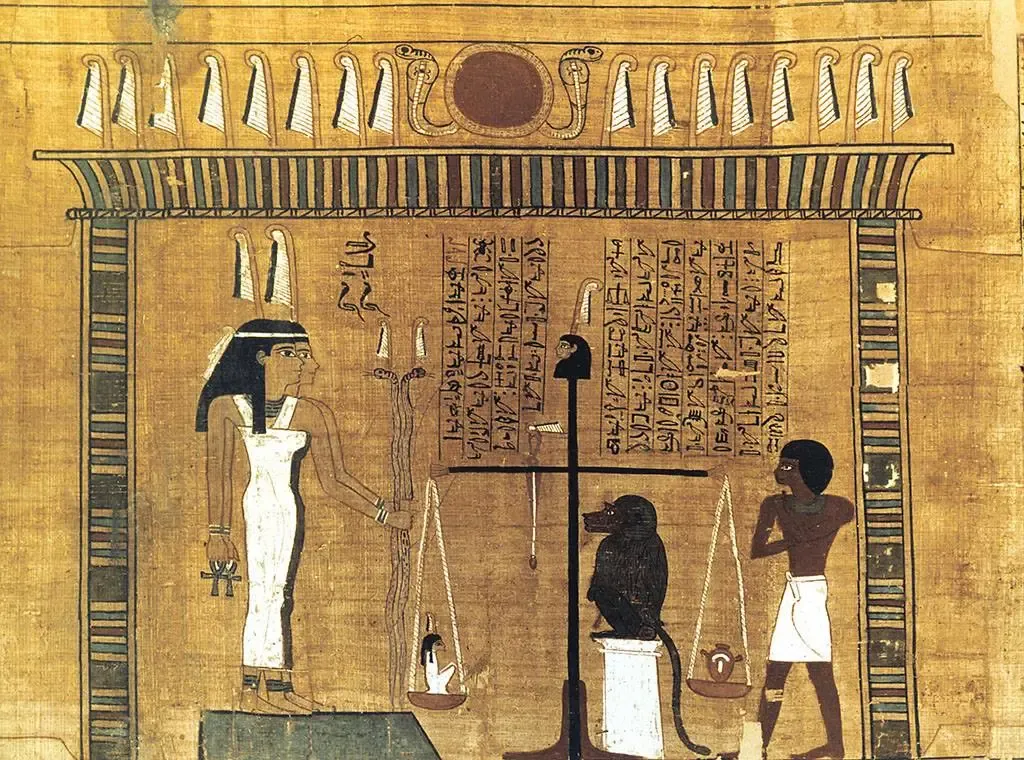

In Ancient Egypt, the heart (not the brain) was believed to house the soul. During mummification, the heart was preserved while the brain was discarded. In the afterlife, the heart was weighed against the feather of Ma’at (truth) to judge the soul’s purity.

In Islamic mysticism, the heart (qalb) is the inner eye, the organ of perception through which divine love flows. The heart is not merely emotional—it is spiritual, a mirror of truth.

In Hinduism, the heart chakra (Anahata) sits at the center of the energetic body. Associated with love, compassion, and balance, it is said to be the bridge between earthly and divine awareness.

In Christian mysticism, the Sacred Heart of Jesus is a flaming symbol of infinite love and mercy, pierced and radiant.

Through each tradition, we see that the heart was never just an organ—it was an axis of being, the portal through which the sacred touches the human.

Romantic Love and the Heart: A Cultural Invention?

It’s often said that romantic love is a relatively modern invention. But the symbol of the heart as an emblem of love dates back at least to the Middle Ages, appearing in 13th-century European manuscripts and troubadour poetry.

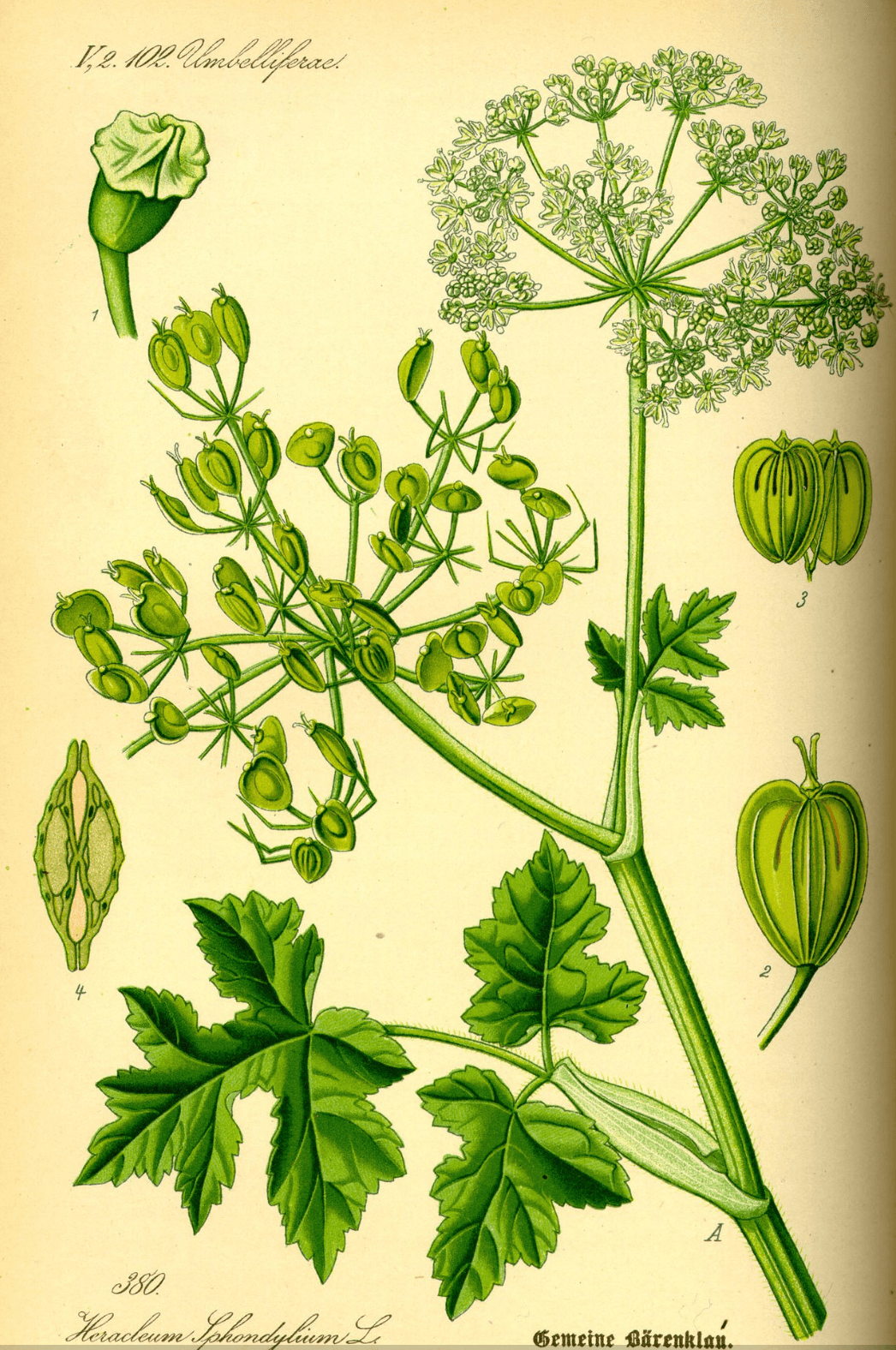

One theory suggests the heart shape may have originated from the silphium plant, used in ancient Cyrene for both medicine and contraception—linking love, fertility, and desire.

By the 15th century, the familiar heart shape was widely used in art, valentines, and love letters. It was a shape of affection and yearning, even as its true anatomical resemblance was vague.

The heart as a symbol persisted because it felt right. After all, the pounding chest, the aching ribs, the rush of warmth—these were not figments. These were experiences of love that lived in the body.

The Broken Heart: Real Pain, Real Healing

Science has confirmed that emotional pain activates the same brain regions as physical pain. Loss or heartbreak isn't “just in your head”—it is registered in your body as suffering.

In extreme cases, intense grief or stress can lead to Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, or “broken heart syndrome,” in which the heart’s left ventricle temporarily weakens. It mimics a heart attack and can even be fatal.

Yet just as the heart can break, it can also heal.

Acts of love—giving, receiving, remembering—regulate heart rhythms, lower cortisol, and restore balance. In this way, love is not only a risk, but a medicine. The heart remembers not only trauma, but tenderness.

Poetry Knows What Science Confirms

“I carry your heart with me (I carry it in

my heart)”

– E.E. Cummings

Poetry has long told the truth that science is only now beginning to quantify: the heart is a sensor, a memory keeper, a resonant field of feeling.

We don’t say “I love you with all my hypothalamus.” We say “with all my heart.” Not because it's logically precise, but because it captures something real—how love makes the center of us feel full, moved, alive.

Love changes the pattern of our heartbeats. It changes the way we breathe, sleep, move, and care. It binds us to others not only emotionally, but physiologically.

A Living Metaphor

So, why is the heart associated with love?

Because it is:

The organ of life, whose rhythm marks our entry and exit from the world;

The resonator of feeling, pulsing to joy or grief;

The bridge between brain and body, sensation and soul;

The symbol through which cultures encode the sacredness of affection, compassion, and unity;

A living metaphor for the human condition: fragile, strong, broken, mended, given.

In truth, love is not only of the heart. It is also of the skin, the gut, the eyes, the breath, and the brain. But the heart is where we locate love because it is where we feel love—in the rise of our chest, the opening of a space inside us, the racing beat that tells us: something is happening here.

To love with the heart is to risk, to soften, and to pulse in harmony with another. It is to be fully alive.

And perhaps that is the secret—why we always return to the heart. Because the heart reminds us that to love is not merely to think or to choose. It is to feel the thrum of life itself, echoing inside us, reminding us we are connected.

previous

Open-Source Seeds: A Revolution for Biodiversity, Farmer Sovereignty, and Food Security

next

Memory’s Ark: Fayez Barakat and His Collection of Cultural Resonance

Share this

Maria Fonseca

Maria Fonseca is an interdisciplinary educator, writer, artist and researcher whose work bridges the realms of academic knowledge, community engagement, and spiritual inquiry. With a background in Fine Art and a doctorate in creative practice, Maria has spent over a decade exploring the intersections of human experience, cultural meaning, and collective transformation.

More Articles

The Digital Convergence: When Images Became Everything, Everywhere, All at Once

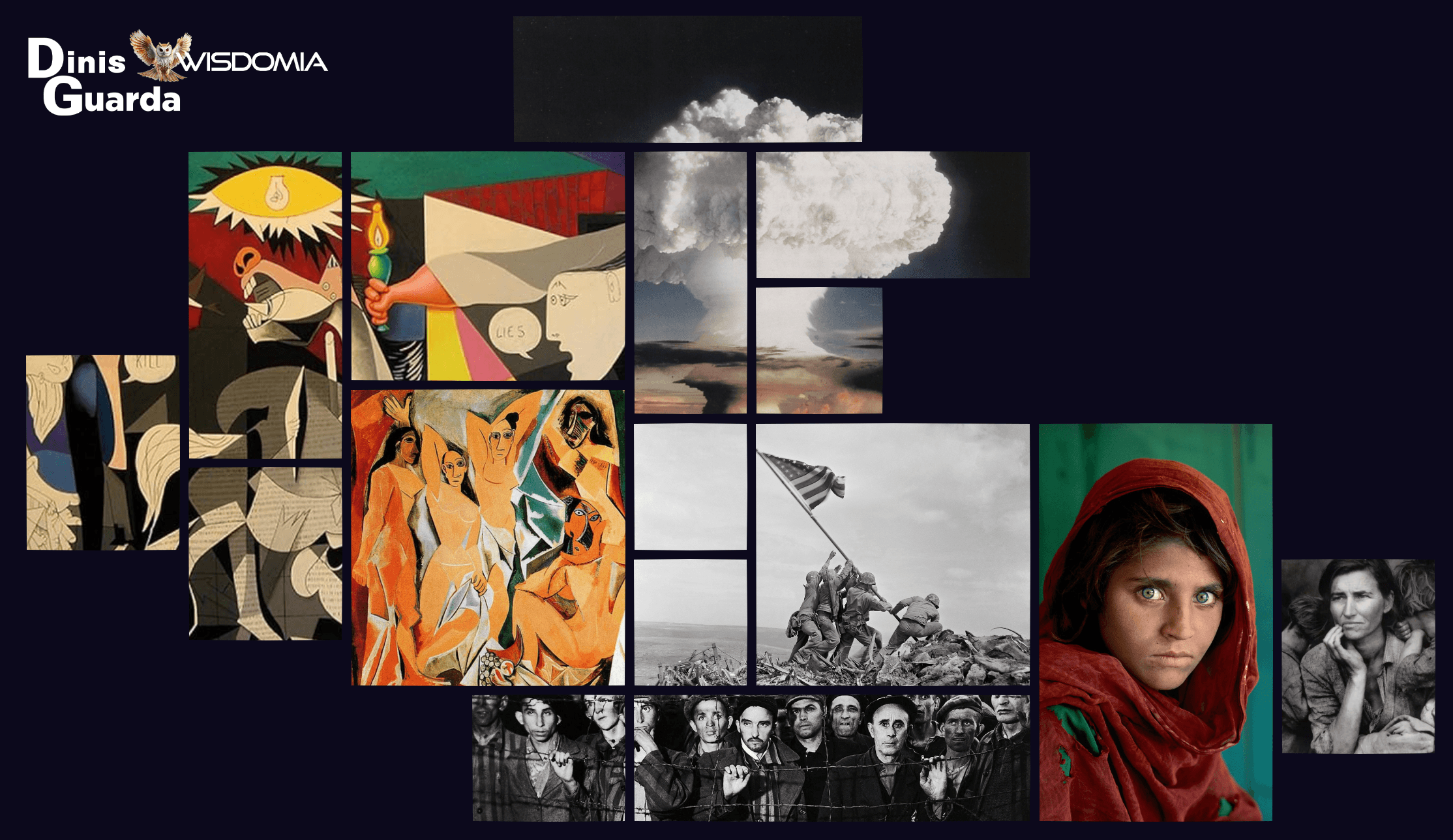

Modern Revolutions and the Digital Explosion: Images That Shattered and Rebuilt Reality

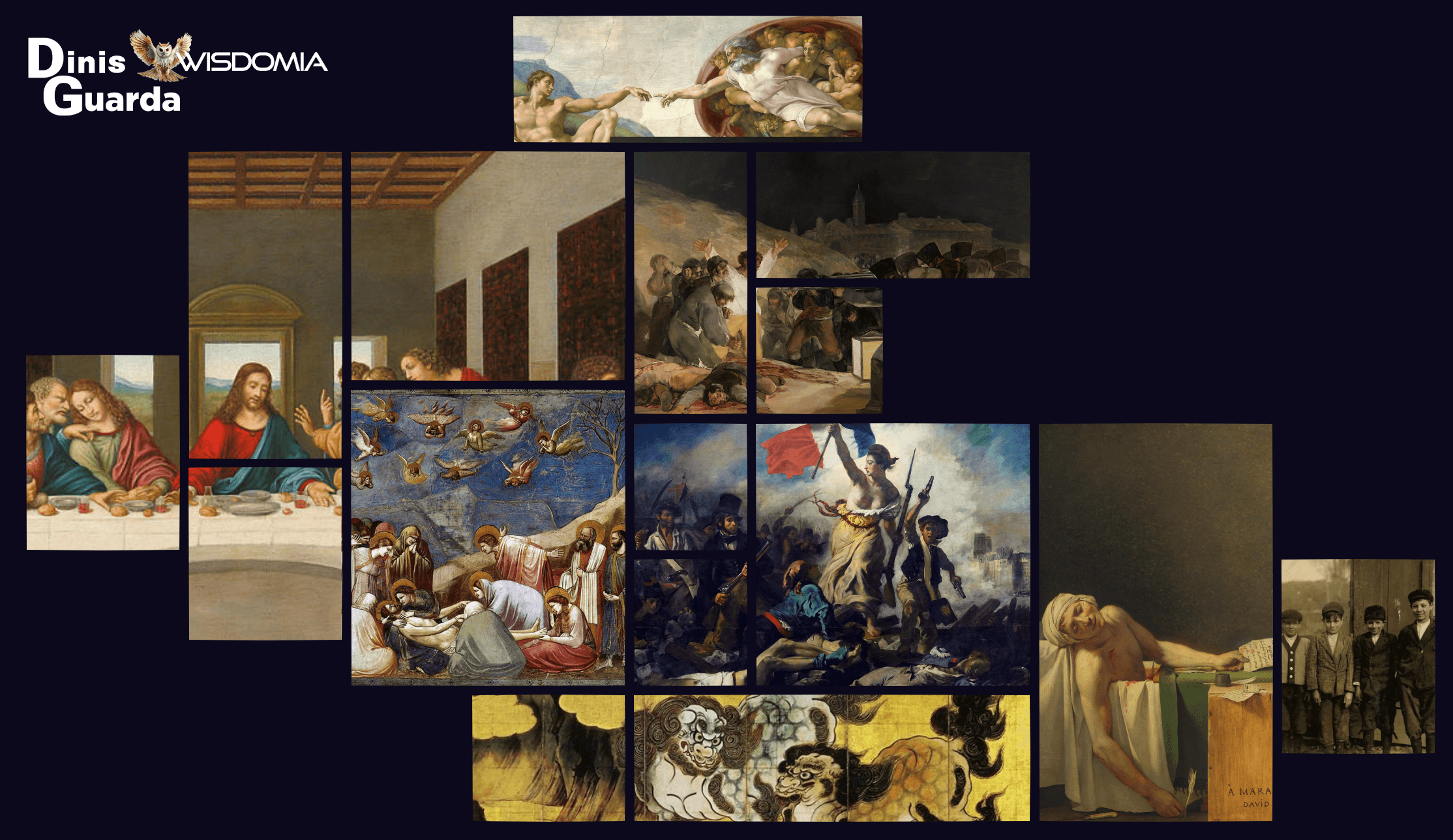

Renaissance Humanism and the Birth of the Modern Gaze: Images That Taught Us to See Ourselves

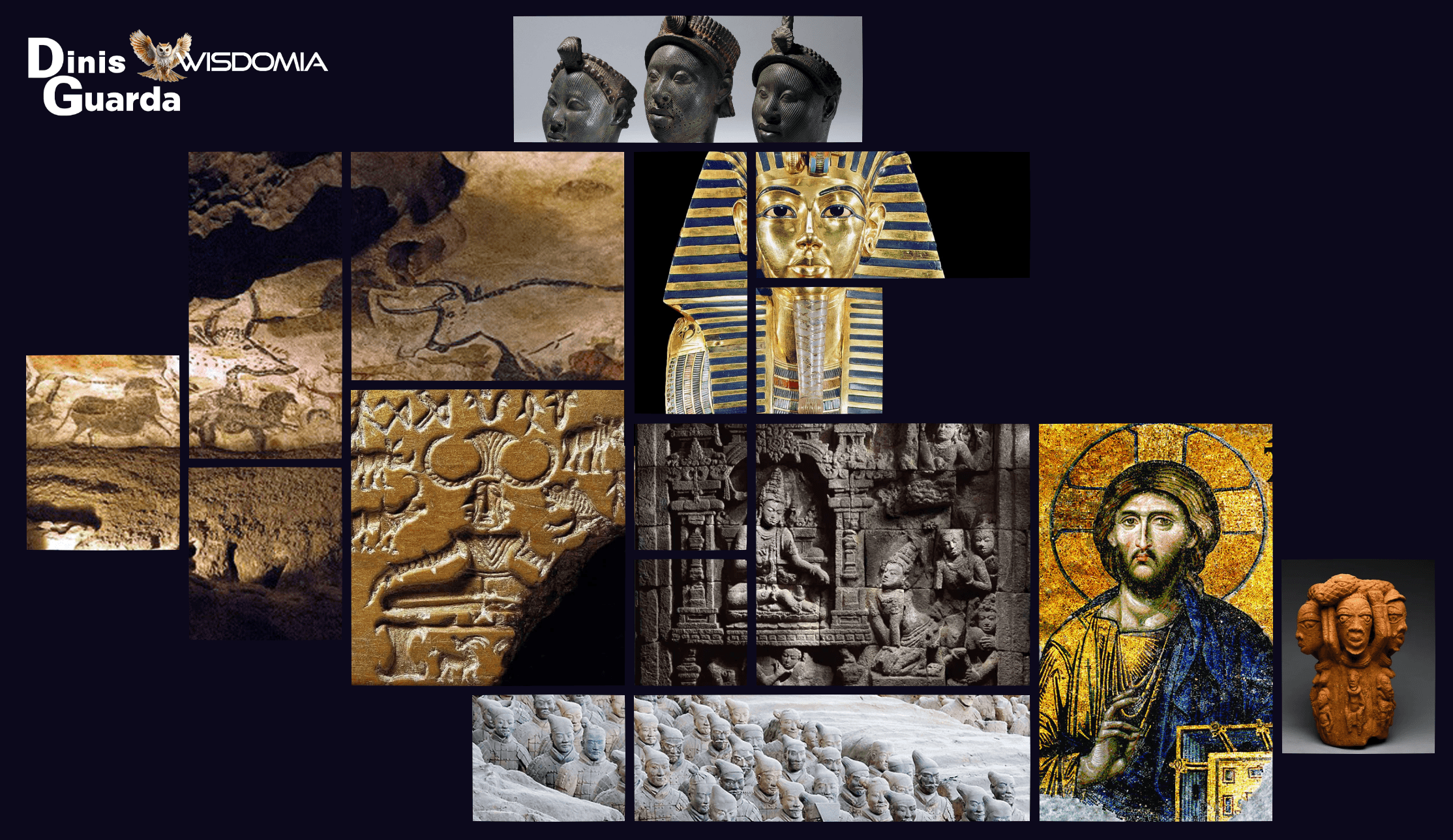

When Vision Becomes Destiny: The First 25 Images That Shaped Human Consciousness

What a Small Indian Village Teaches the World About Sustainability