Open-Source Seeds: A Revolution for Biodiversity, Farmer Sovereignty, and Food Security

Maria Fonseca

Mon Jul 21 2025

Open-source seeds are a movement to protect seeds as a shared, living heritage—free to use, save, and share without corporate patents. Inspired by the open-source software model, they promote biodiversity, farmer sovereignty, and climate resilience. Initiatives like OSSI in the U.S. and OpenSourceSeeds in Germany are pioneering legal tools to prevent privatization of plant life. This movement challenges industrial agriculture and envisions a more just, regenerative food system rooted in freedom and care.

In an era dominated by industrial agriculture and multinational corporations controlling the global seed market, the concept of open-source seeds offers a refreshing and powerful alternative. Inspired by the ethos of open-source software, this movement seeks to reclaim seeds as a shared heritage—free to use, share, and improve by anyone, without the constraints of patents or proprietary restrictions. As concerns about biodiversity loss, corporate monopolies, and food security deepen, open-source seeds emerge not only as a legal innovation but also as a cultural and ecological imperative.

The Problem: Corporate Control Over Seeds

Today, the global seed industry is concentrated in the hands of a few large agrochemical and biotech corporations. Companies such as Bayer (which acquired Monsanto), Syngenta, Corteva, and Limagrain collectively control a significant majority of the commercial seed market worldwide. This concentration has profound implications:

Patented Seeds: Corporations invest heavily in developing genetically modified (GM) seeds or hybrid varieties and then protect their investments through patents or plant variety protections. Farmers who purchase these seeds are often legally prohibited from saving and replanting seeds from their harvest, forcing them into a cycle of buying seeds every season.

Loss of Seed Sovereignty: This system undermines the traditional practices of farmers saving, exchanging, and breeding seeds—practices that have sustained agriculture for millennia.

Reduced Biodiversity: Corporate seed systems tend to promote uniform, high-yielding varieties optimized for large-scale industrial agriculture. This leads to monocultures that reduce genetic diversity, making crops more vulnerable to pests, diseases, and climate change.

Dependency and Inequality: Smallholder farmers, especially in the Global South, often become dependent on expensive seeds and agrochemicals, exacerbating economic inequalities and social vulnerabilities.

Given this context, the open-source seed movement is a deliberate pushback against corporate control, aiming to democratize access to seeds and restore agricultural resilience.

What Are Open-Source Seeds?

The idea of open-source seeds is modeled after the open-source software movement, where programmers freely share code that others can use, modify, and redistribute, provided they keep it open. Applied to seeds, this concept entails:

Freedom to Use: Farmers, gardeners, and breeders can freely grow, save, exchange, and sell open-source seeds.

No Patent Restrictions: The seeds—and any new varieties bred from them—cannot be patented or otherwise restricted by intellectual property rights.

Viral Protection: Often, open-source seed licenses or pledges require that anyone who develops new varieties from these seeds must also keep them free and open, preventing privatization down the line.

This legal and ethical framework ensures that seeds remain a commons, a shared resource accessible to all.

Leading Open-Source Seed Initiatives

1. The Open Source Seed Initiative (OSSI) — United States

Founded in 2012 by a coalition of plant breeders, seed companies, farmers, and activists, OSSI was the first to formalize the concept of open-source seeds in agriculture. Their approach is based on a simple yet powerful “pledge” that accompanies the seeds:

“You have the freedom to use these OSSI-Pledged seeds in any way you choose. In return, you pledge not to restrict others’ use of these seeds or their derivatives by patents or other means, and to include this pledge with any transfer of these seeds or their derivatives.”

This pledge acts as a social contract encouraging a culture of sharing and openness without relying on complex legal instruments. OSSI focuses on a wide range of crops, including vegetables, grains, and flowers, and has inspired a growing network of breeders and seed companies.

2. OpenSourceSeeds — Germany

A project of the NGO Agrecol, OpenSourceSeeds launched in 2017 to extend the open-source seed model with a legally binding license under German law. This license requires downstream users to keep seeds and their derivatives free from intellectual property claims.

OpenSourceSeeds has introduced several open-source varieties, such as “Sunviva”, a flavorful tomato bred specifically for taste, not industrial uniformity. This approach blends traditional breeding with modern legal tools to protect seed freedom.

3. Navdanya — India

Founded by environmentalist and activist Dr. Vandana Shiva, Navdanya is not strictly an open-source seed initiative in the legal sense but shares the same spirit of seed freedom. Navdanya supports:

Community seed banks preserving indigenous and traditional varieties.

Farmer-led breeding and seed sharing.

Active resistance to seed patents and genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

Navdanya highlights the cultural and spiritual dimensions of seeds as “living ancestors” and champions biodiversity as a pathway to food sovereignty.

Why Open-Source Seeds Matter

Biodiversity Conservation and Climate Resilience

Genetic diversity in crops is the foundation of resilient agriculture. Open-source seeds encourage breeding and preservation of locally adapted varieties, many of which have evolved over centuries to thrive in specific environments. This diversity:

Improves resilience to pests, diseases, and extreme weather.

Supports ecosystem services such as pollination and soil health.

Provides farmers with options to adapt to changing climates.

Industrial seed systems, by contrast, tend to favor uniform, high-yield varieties that can fail catastrophically under stress.

Farmer Sovereignty and Empowerment

Open-source seeds restore power to farmers by:

Allowing them to save and exchange seeds freely without legal threats.

Supporting farmer innovation and traditional knowledge.

Reducing dependency on expensive corporate seeds and chemicals.

This empowerment can improve livelihoods and strengthen rural communities.

Ethical and Cultural Dimensions

Seeds are not merely commodities; they are carriers of culture, tradition, and identity. Open-source seeds affirm the idea that seeds are a commons, belonging to all humanity rather than a few corporations. This aligns with:

Indigenous worldviews seeing seeds as sacred.

Movements for food justice and ecological stewardship.

Principles of reciprocity, sharing, and sustainability.

Challenges Facing the Movement

Despite its promise, the open-source seed movement faces significant obstacles:

Limited Funding: Public and philanthropic funding for open-source breeding is modest compared to corporate R&D budgets.

Regulatory Barriers: Seed laws and certification requirements can favor industrial seed companies and complicate distribution of diverse or non-uniform varieties.

Market Access: Open-source seeds often rely on niche markets, small-scale farmers, or home gardeners, limiting scale.

Farmer Awareness: Many farmers may not be familiar with open-source principles or have access to open-source seed networks.

Overcoming these challenges requires supportive policies, community education, and collaboration between breeders, farmers, and consumers.

The Future of Open-Source Seeds

As concerns about climate change, corporate control, and food security grow, open-source seeds offer a hopeful path forward. Some emerging trends include:

Integration with Agroecology: Open-source seeds complement agroecological farming practices that emphasize biodiversity, soil health, and ecological balance.

Digital Seed Sharing: Some initiatives explore digital platforms and seed libraries to facilitate open sharing and collaboration.

Legal Innovations: New licenses and seed sovereignty laws are being developed to protect seed freedom internationally.

Global Solidarity: Networks of seed savers, indigenous communities, farmers, and activists are forging transnational alliances.

Ultimately, open-source seeds are about reclaiming agency—the power to shape how food is grown and shared. They reconnect us to the wisdom of seeds themselves: rooted in the earth, evolving with care, and thriving through diversity.

The story of open-source seeds is a story of resistance and renewal. It challenges the privatization of life’s foundational resource and envisions a future where seeds remain free—alive in the hands of farmers, gardeners, and communities worldwide. By embracing openness, biodiversity, and shared responsibility, open-source seeds inspire a more just, sustainable, and resilient food system for generations to come.

previous

Why Is the Ocean Blue? The Simple Science Behind Water’s Color

next

Why Is the Heart Associated with Love?

Share this

Maria Fonseca

Maria Fonseca is an interdisciplinary educator, writer, artist and researcher whose work bridges the realms of academic knowledge, community engagement, and spiritual inquiry. With a background in Fine Art and a doctorate in creative practice, Maria has spent over a decade exploring the intersections of human experience, cultural meaning, and collective transformation.

More Articles

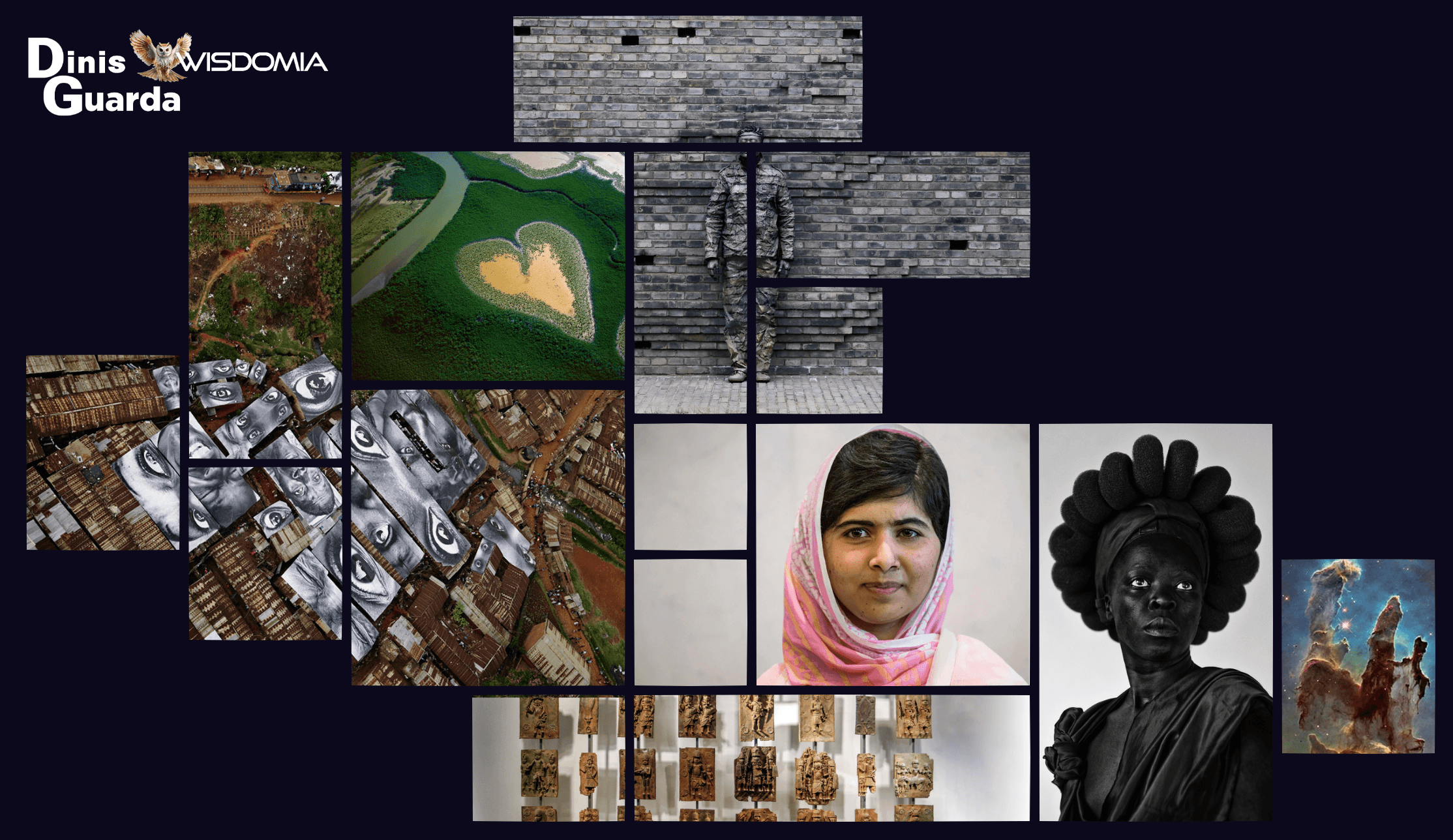

The Digital Convergence: When Images Became Everything, Everywhere, All at Once

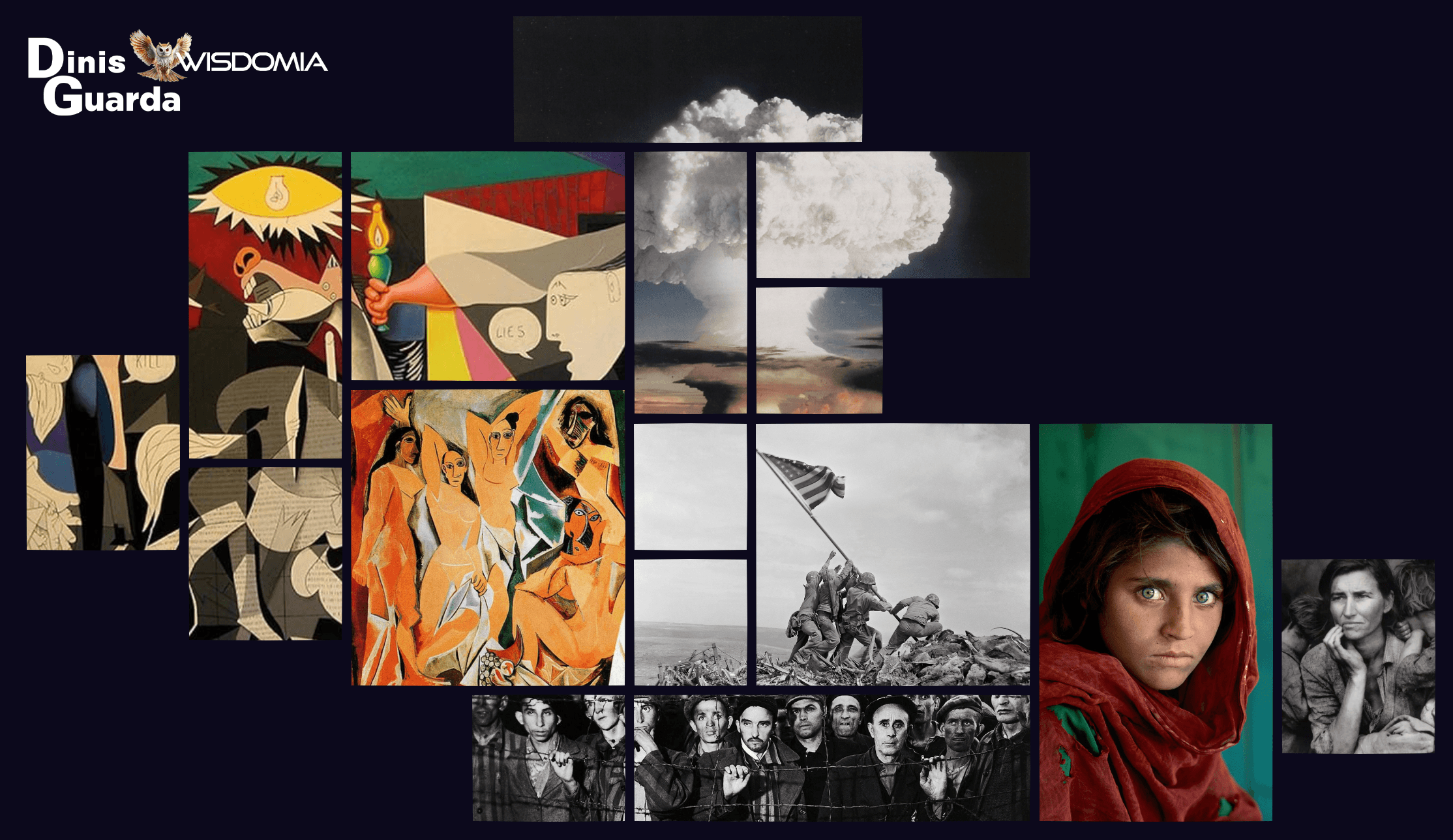

Modern Revolutions and the Digital Explosion: Images That Shattered and Rebuilt Reality

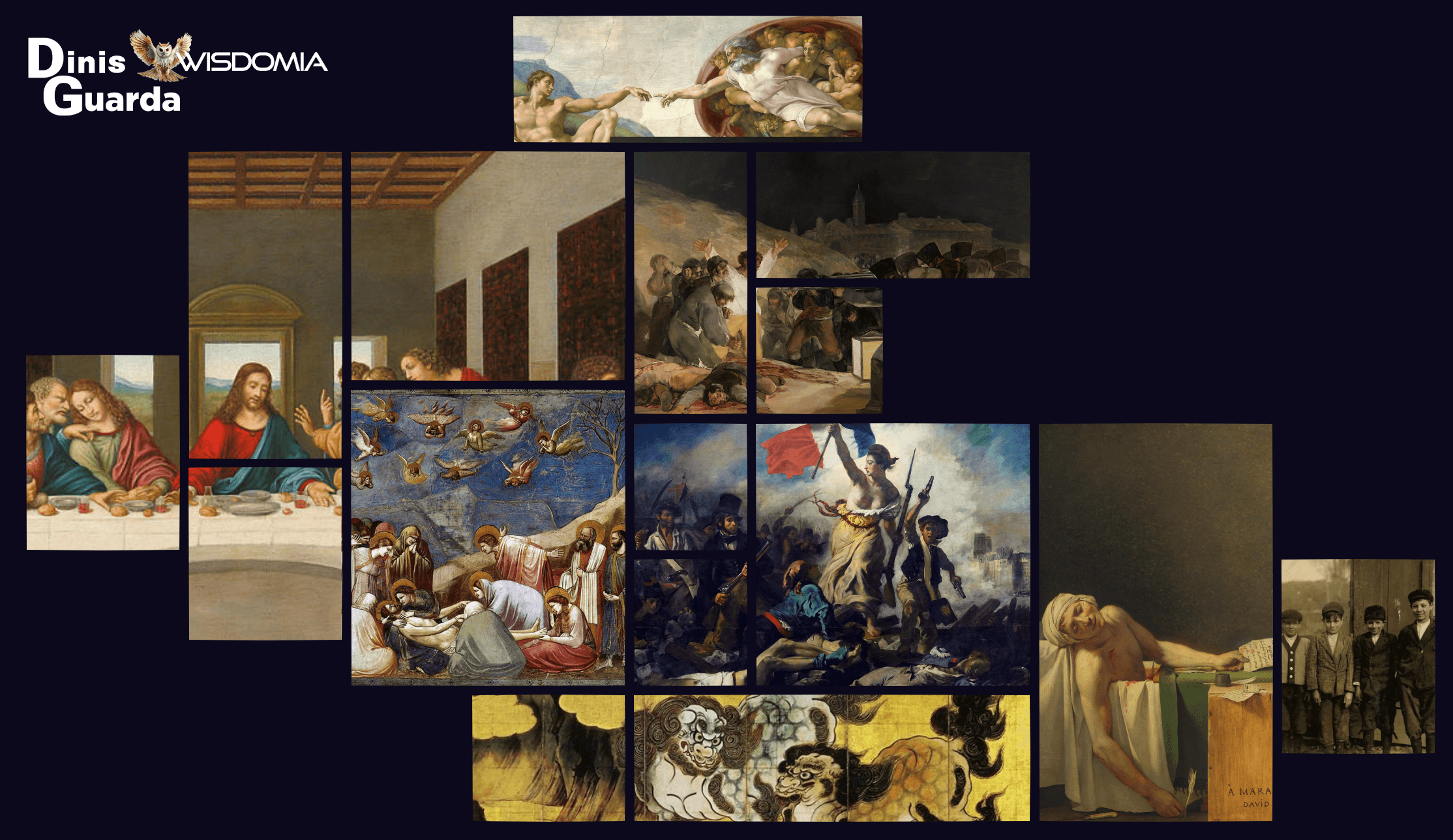

Renaissance Humanism and the Birth of the Modern Gaze: Images That Taught Us to See Ourselves

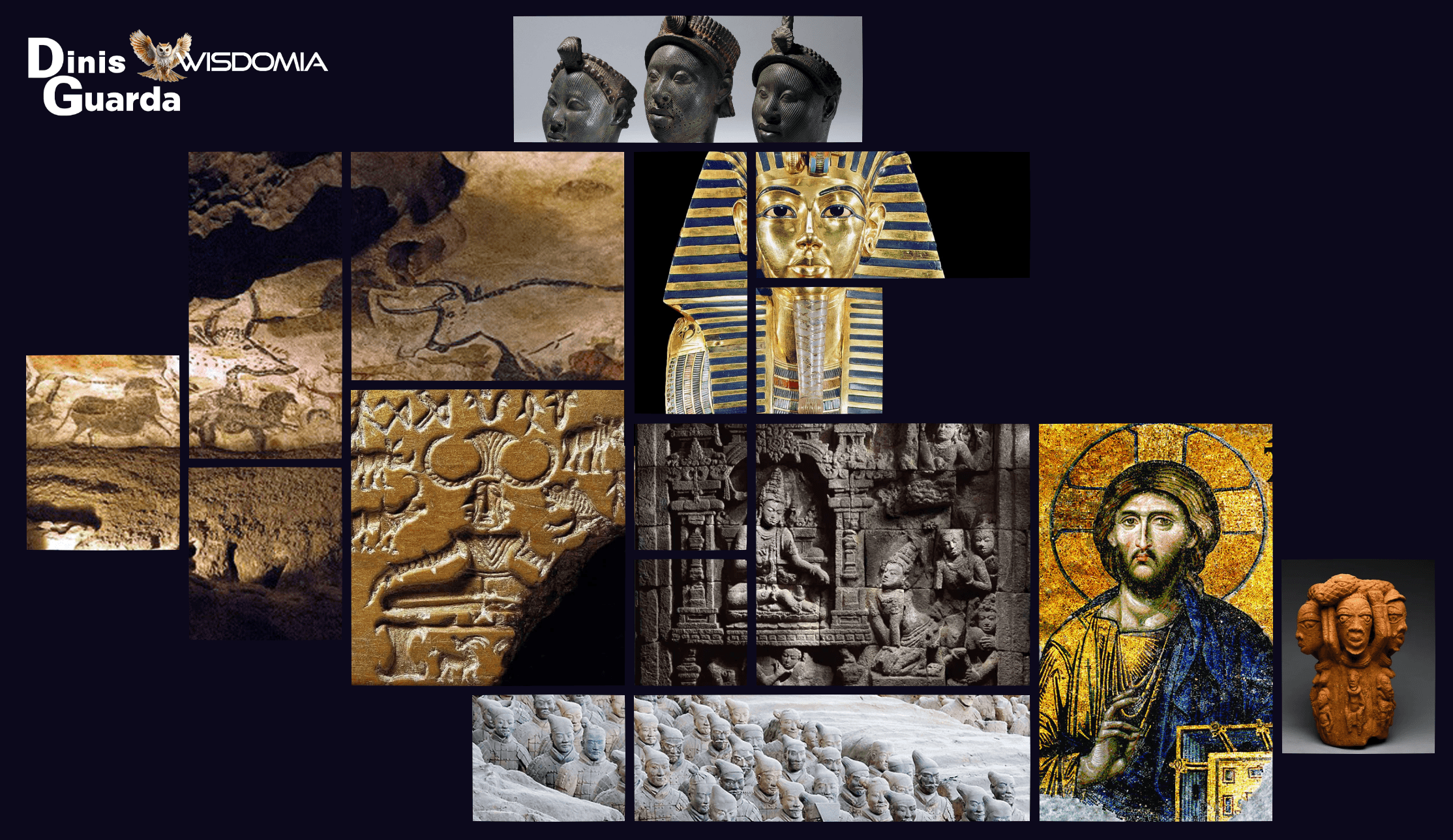

When Vision Becomes Destiny: The First 25 Images That Shaped Human Consciousness

What a Small Indian Village Teaches the World About Sustainability