What Would a Wise Economy Look Like? Welcome to Doughnut Economics

Sara Srifi

Fri Nov 07 2025

GDP growth is destroying the planet. Doughnut Economics offers a wiser path: prosperity for all within Earth's limits. Discover the framework changing cities.

Imagine an economy that doesn't grow for growth's sake, that doesn't measure success by GDP alone, and that actually works for both people and planet. Sound impossible? Kate Raworth, an Oxford economist, has designed exactly that, and she's visualized it as a doughnut.

Yes, a doughnut. Not the glazed kind, but a revolutionary framework that's changing how cities, businesses, and governments think about economic success. And it might just be the wisest economic model humanity has ever conceived.

In a world facing climate catastrophe, widening inequality, and systems that seem fundamentally broken, Doughnut Economics offers something rare: a vision of prosperity that doesn't cost the Earth. Literally.

But what exactly is this doughnut? How does it work? And why are cities from Amsterdam to Philadelphia embracing it as a blueprint for the future?

The Problem with How We Measure Success

To understand why we need a new economic model, we first need to recognize what's wrong with the current one.

For decades, nations have measured economic success primarily through Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the total value of goods and services produced. If GDP grows, we're told the economy is healthy. Politicians campaign on GDP growth. Markets respond to GDP numbers. Our entire economic story revolves around this single metric.

But here's the problem: GDP measures everything except what actually matters.

GDP counts pollution cleanup as economic growth. It counts prison construction, cigarette sales, and environmental destruction as positive contributions. Meanwhile, GDP ignores unpaid care work (mostly done by women), ecosystem services that sustain life, and the depletion of natural resources that future generations will need.

An economy can have stellar GDP growth while inequality explodes, mental health crises deepen, ecosystems collapse, and millions struggle to meet basic needs. We've confused growth with prosperity, expansion with wellbeing, more with better.

The Infinite Growth Delusion

Perhaps the most fundamental flaw in conventional economics is its assumption that infinite growth is possible, and desirable, on a finite planet.

This assumption made sense in the 18th and 19th centuries when economists like Adam Smith were developing theories. The world seemed vast and limitless. Resources appeared inexhaustible. The environmental consequences of economic activity weren't yet visible on a planetary scale.

But we now live in what scientists call the Anthropocene, an era where human activity shapes Earth's systems. We've pushed past multiple planetary boundaries. Climate change, biodiversity loss, ocean acidification, and nitrogen cycle disruption threaten the ecological foundations that all economies depend on.

Yet our economic models still operate as if Earth's resources and capacity to absorb pollution are infinite. It's like having a business plan that ignores your bank account balance—eventually, reality catches up.

Enter the Doughnut: A Safe and Just Space for Humanity

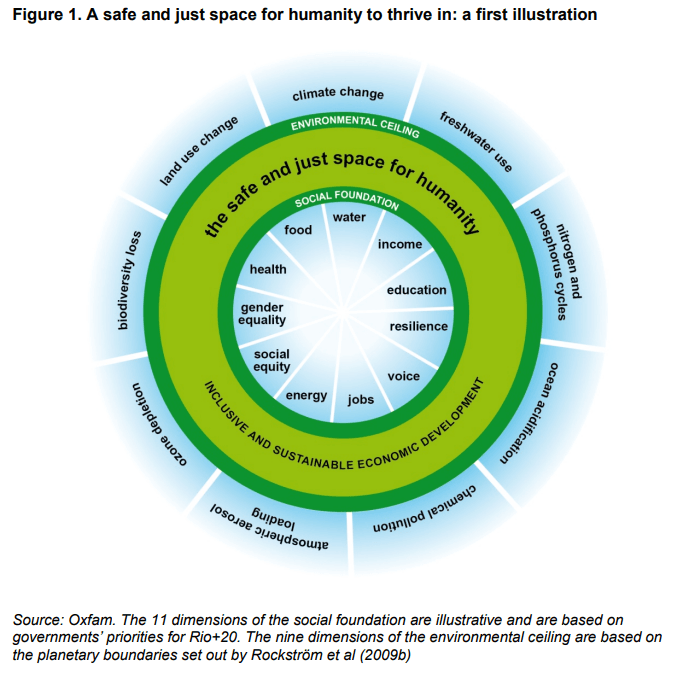

In 2012, Kate Raworth was working at Oxfam when she created a simple diagram that would transform economic thinking. She drew two concentric circles, creating a shape that looks like, you guessed it, a doughnut.

This elegant visual captures what a truly wise economy must achieve: meeting the needs of all people within the means of the planet.

The Inner Ring: The Social Foundation

The doughnut's inner boundary represents the social foundation—the minimum standards of wellbeing that everyone needs to live a good life. Fall below this inner ring, and people experience deprivation, suffering, and exclusion.

Raworth identifies twelve essential dimensions of this social foundation:

- Food means access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious sustenance. Over 800 million people currently fall into the doughnut's hole here, facing hunger and malnutrition.

- Water refers to clean, accessible drinking water and sanitation. Billions lack reliable access to this most basic necessity.

- Health encompasses healthcare access, life expectancy, and freedom from preventable disease.

- Education means not just literacy but genuine learning opportunities that develop human potential.

- Income and work provide economic security and meaningful employment with fair wages.

- Peace and justice create safety from violence and access to legal protections and political voice.

- Political voice ensures participation in decisions that affect your life and community.

- Social equity means freedom from discrimination based on gender, race, ethnicity, or other identity factors.

- Gender equality addresses the specific barriers and violence women face worldwide.

- Housing provides safe, affordable shelter, a foundation for stability and wellbeing.

- Networks represent the social connections and community support essential for human flourishing.

- Energy means access to reliable, affordable power for cooking, heating, lighting, and connection.

Currently, billions of people fall short on one or more of these dimensions. They're living in the doughnut's hole, the place of deprivation. A wise economy, Raworth argues, must lift everyone above this social foundation.

The Outer Ring: The Ecological Ceiling

The doughnut's outer boundary represents the ecological ceiling, the planetary boundaries we cannot safely cross without triggering dangerous environmental changes.

Based on the groundbreaking work of Earth system scientist Johan Rockström and colleagues, this ceiling includes nine critical planetary boundaries:

- Climate change is perhaps the most urgent. We've already warmed the planet over 1°C, with devastating consequences becoming increasingly visible.

- Ocean acidification occurs as oceans absorb excess CO2, threatening marine ecosystems and the billions who depend on them.

- Chemical pollution includes plastics, pesticides, and synthetic substances accumulating in ecosystems and bodies.

- Nitrogen and phosphorus loading from agricultural runoff creates dead zones in oceans and lakes.

- Freshwater withdrawals are depleting aquifers and rivers faster than they can replenish.

- Land conversion destroys forests, wetlands, and grasslands, eliminating habitat and ecosystem services.

- Biodiversity loss is proceeding at rates comparable to mass extinctions in Earth's geological past.

- Air pollution kills millions annually while degrading ecosystems.

- Ozone layer depletion has improved due to international action, but remains a boundary requiring vigilance.

We've already transgressed at least six of these nine boundaries. We're overshooting the ecological ceiling, living beyond Earth's means, accumulating an environmental debt that threatens collapse.

The Sweet Spot: Between the Rings

The space between the inner and outer rings. the doughnut itself, represents the safe and just space for humanity. This is where a wise economy operates.

In this space, everyone's needs are met (we're above the social foundation) while we're living within Earth's ecological limits (we're below the ecological ceiling). This is the sweet spot where human prosperity and planetary health coexist.

Currently, no nation on Earth achieves this. Wealthy countries meet most social needs but catastrophically overshoot ecological boundaries. Poor countries generally stay within ecological boundaries but fail to meet basic social needs. We're all either in the hole or over the edge—and often both.

The great challenge of the 21st century, Raworth argues, is getting into the doughnut and staying there. This requires fundamentally rethinking economic goals, measures, and systems.

The Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist

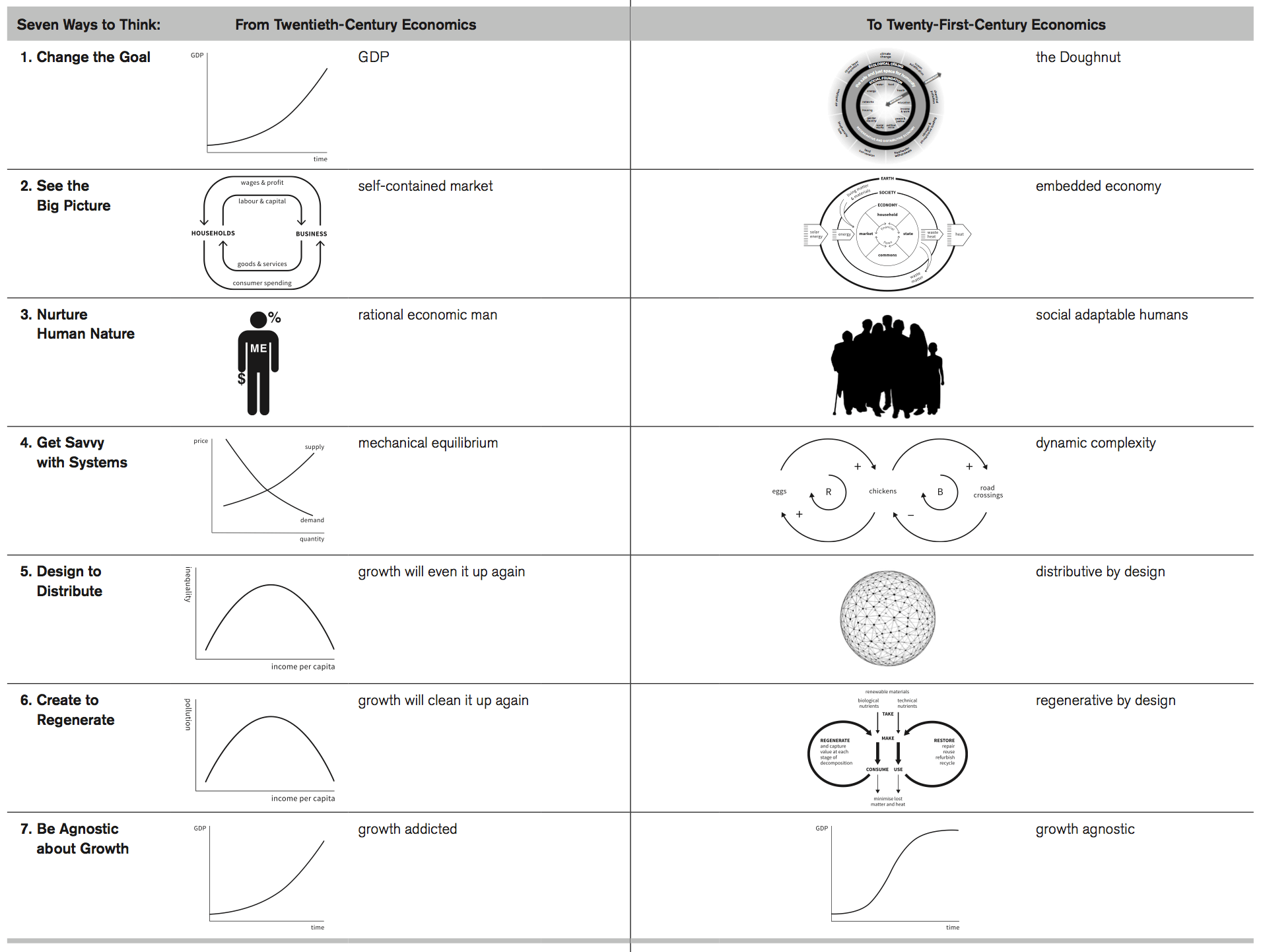

Raworth's book, "Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist," doesn't just critique conventional economics, it offers alternative ways of thinking that can help us design wiser systems.

1. Change the Goal: From GDP Growth to the Doughnut

The first shift is the most fundamental: redefine the purpose of economics itself.

20th-century economics was obsessed with GDP growth as the primary goal. But as Robert F. Kennedy famously said in 1968, GDP "measures everything except that which makes life worthwhile."

Instead of asking "How do we achieve maximum GDP growth?" a wise economy asks: "How do we enable all people to thrive within planetary boundaries?"

This changes everything. Policies that increase GDP but degrade ecosystems or deepen inequality fail the doughnut test. Approaches that enhance wellbeing while regenerating nature succeed, even if they don't maximize GDP.

2. See the Big Picture: From Market-Centric to Embedded Economy

Conventional economics places markets at the center of everything, treating the economy as separate from society and nature.

Doughnut Economics recognizes that the economy is embedded within society, which is embedded within the living world. Markets are just one piece of a larger system that includes households, commons, the state, and the biosphere.

This means recognizing that unpaid care work (mostly done by women) is economically essential, even if markets don't value it. It means understanding that healthy ecosystems provide services, pollination, water filtration, climate regulation, that no market can replace. It means seeing that social trust and cooperation enable market transactions.

A wise economy designs policies that strengthen all these domains, not just markets.

3. Nurture Human Nature: From Rational Economic Man to Social Adaptable Humans

Economics has long assumed humans are rational, self-interested individuals who make calculated decisions to maximize personal benefit, the famous "homo economicus."

But decades of behavioral research and evolutionary biology show this is fiction. Humans are actually social, interdependent beings with complex motivations including reciprocity, fairness, altruism, and meaning-seeking.

We're also adaptable. Our values and behaviors are shaped by the systems and cultures we live within. Create systems that reward selfishness, and people become selfish. Design systems that enable cooperation and generosity, and different behaviors emerge.

A wise economy designs institutions that bring out humanity's cooperative, creative, and caring capacities rather than assuming we're narrow self-maximizers.

4. Get Savvy with Systems: From Mechanical Equilibrium to Dynamic Complexity

Traditional economics borrowed metaphors from 19th-century physics, imagining the economy as a machine that naturally moves toward equilibrium, a stable, predictable state.

But economies are actually complex adaptive systems, more like ecosystems than machines. They're characterized by feedback loops, tipping points, emergence, and path dependence. Small changes can cascade into large effects. History matters. Equilibrium is rare.

Understanding this complexity changes how we approach policy. Instead of seeking to "fix" the economy and return it to equilibrium, we learn to work with system dynamics, identifying leverage points, managing feedback loops, building resilience, and enabling positive transformations.

This systems thinking is essential for navigating challenges like climate change, where tipping points could trigger irreversible changes.

5. Design to Distribute: From "Growth Will Even It Out" to Distributive by Design

Conventional economics claimed that growth would eventually "trickle down" to benefit everyone. Just make the economic pie bigger, the thinking went, and everyone's slice grows.

This hasn't happened. Instead, over recent decades, inequality has exploded as wealth concentrates among the already wealthy. The richest 1% have captured a vastly disproportionate share of growth while billions remain in poverty.

Doughnut Economics argues we must design economies to be distributive from the start, to spread value creation, ownership, and power widely rather than hoping it will trickle down.

This means rethinking:

- Ownership structures: Promoting cooperatives, employee ownership, and community land trusts alongside traditional corporations

- Intellectual property: Balancing innovation incentives with open-source approaches that spread knowledge

- Technology design: Ensuring platforms and algorithms don't concentrate wealth among tech oligarchs

- Financial systems: Directing finance toward productive investment rather than extractive rent-seeking

- Tax policy: Progressive taxation that redistributes wealth and funds public goods

6. Create to Regenerate: From "Growth Will Clean It Up" to Regenerative by Design

Just as conventional economics assumed growth would distribute wealth, it assumed growth would eventually solve environmental problems. Once rich enough, the thinking went, societies would clean up pollution and protect nature.

Again, this hasn't happened. Wealthy nations are the biggest ecological overshooters, consuming resources and generating pollution far beyond sustainable levels.

Doughnut Economics calls for regenerative design—systems that restore and renew rather than deplete and degrade. Instead of "take-make-waste" linear systems, we need circular flows that eliminate waste, restore soil health, rebuild biodiversity, and draw down carbon.

This means:

- Circular economy: Designing products for durability, repair, and cycling of materials

- Regenerative agriculture: Farming practices that rebuild soil, sequester carbon, and enhance ecosystems

- Renewable energy: Powering society with flows (sun, wind, water) rather than stocks (fossil fuels)

- Biomimicry: Learning from nature's 3.8 billion years of design experience

- Commons management: Stewarding shared resources (forests, fisheries, atmosphere) collectively

The goal isn't just sustainability, maintaining what we have, but regeneration: actively healing the damage already done.

7. Be Agnostic About Growth: From Growth-Addicted to Growth-Agnostic

Perhaps the most radical shift in Doughnut Economics is becoming agnostic about GDP growth, treating it as neither goal nor enemy, but simply as one metric among many.

In wealthy, high-income nations that have already overshot ecological boundaries, continued GDP growth is likely ecologically impossible and socially unnecessary. These countries need to focus on redistributing what they have and transitioning to regenerative systems, whether GDP grows, shrinks, or stays flat.

For lower-income nations still below the social foundation, some growth may be necessary to meet basic needs. But the path should be regenerative from the start, not a repeat of destructive industrialization patterns.

The key question shifts from "How do we achieve growth?" to "How do we thrive?" A wise economy enables human flourishing whether or not GDP rises. It measures success by how many people are in the doughnut, not by aggregate production.

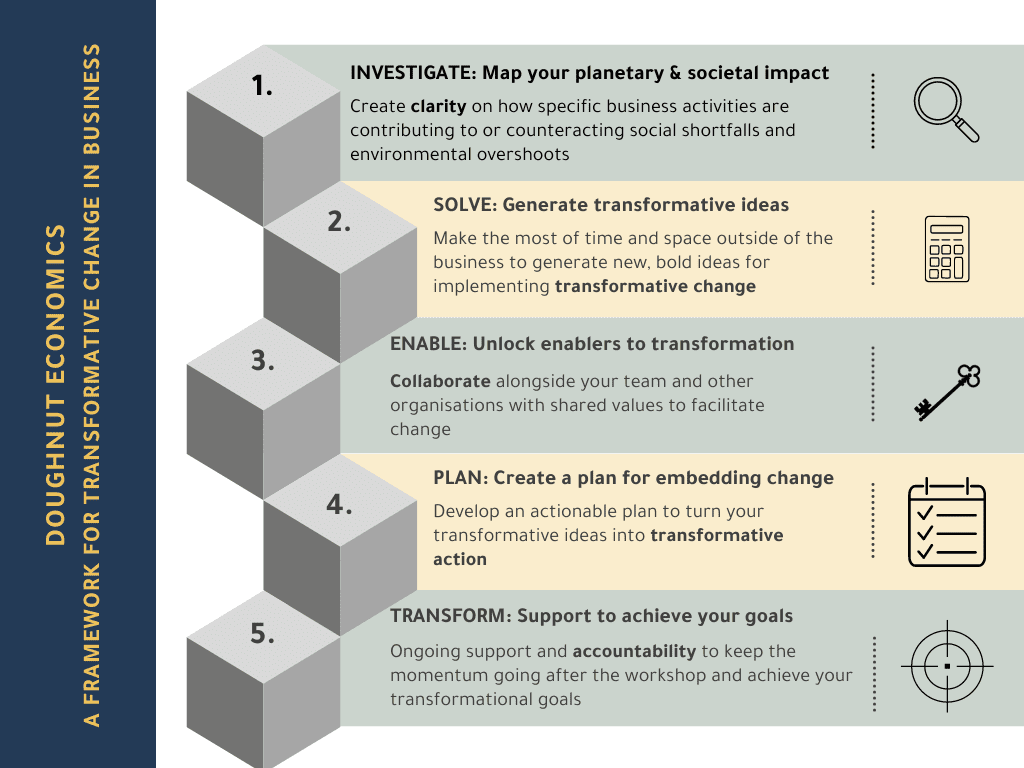

Doughnut Economics in Action: Real-World Examples

The beauty of Doughnut Economics isn't just theoretical, cities, regions, and organizations worldwide are putting it into practice.

Amsterdam: The First Doughnut City

In April 2020, Amsterdam became the first city to officially adopt Doughnut Economics as a framework for recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and transition toward sustainability.

The city created a "portrait" showing where Amsterdam's 900,000 residents stand relative to the doughnut's social foundation and ecological ceiling. This revealed specific shortfalls and overshoots, for example, strong performance on education but overshooting on carbon emissions and material consumption.

Amsterdam then developed concrete strategies organized around four key transformations:

- Circular economy initiatives aim to halve raw material use by 2030. The city promotes product-as-service models, shared consumption, and design for circularity across construction, food systems, and consumer goods.

- Regenerative food systems focus on shortening supply chains, supporting organic farming, reducing food waste, and making nutritious food accessible to all residents.

- Inclusive prosperity programs ensure economic opportunities reach marginalized communities through social enterprises, community wealth building, and skills development.

- Climate-neutral infrastructure investments transform buildings, transportation, and energy systems to eliminate carbon emissions while creating green jobs.

Rather than top-down mandates, Amsterdam works collaboratively with businesses, community groups, and residents to co-create solutions. The doughnut provides a shared language and vision that aligns diverse stakeholders.

Other Cities Joining the Movement

Amsterdam isn't alone. Cities including Copenhagen, Portland, Philadelphia, Brussels, and Dunedin have embraced Doughnut Economics.

- Copenhagen uses the framework to guide its ambitious climate action plan and transition to carbon neutrality.

- Philadelphia applies doughnut thinking to address persistent poverty and racial inequality while building climate resilience.

- Barcelona integrates the doughnut into neighborhood planning, focusing on community needs and ecological regeneration.

The Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL) supports these efforts, providing tools, training, and connections to help cities and communities implement doughnut principles.

Costa Rica: National-Level Application

At the national level, Costa Rica has embraced many doughnut principles, though not always under that name. The country has achieved impressive social outcomes, universal healthcare, high literacy, strong democratic institutions, while running on 99% renewable electricity and protecting 25% of its land for conservation.

Costa Rica demonstrates that ecological regeneration and human wellbeing can advance together. While challenges remain, inequality and ecological pressures persist, the country offers proof that alternative development paths are possible.

Businesses Embracing Circular Models

Companies worldwide are adopting circular economy principles central to doughnut thinking:

Patagonia designs products for durability and repair, runs a worn wear program for used gear, and uses recycled materials extensively.

Interface, a carpet manufacturer, has eliminated waste sent to landfills and developed carpet tiles designed for complete recycling.

Fairphone creates smartphones designed for longevity, repairability, and ethical sourcing of materials.

These businesses prove that regenerative practices can coexist with commercial success—in fact, often enhancing it through innovation, customer loyalty, and resilience.

Criticisms and Challenges

Like any transformative idea, Doughnut Economics faces critiques worth examining.

The Measurement Challenge

Critics point out that defining and measuring the social foundation and ecological ceiling involves complex value judgments. What level of income constitutes sufficiency? How do we weight different planetary boundaries? Different cultures might answer differently.

Raworth acknowledges this, arguing the doughnut isn't a precise formula but a flexible framework that each community must adapt to its context. The key is having the conversation about what constitutes enough, something conventional economics ignores entirely.

Political Feasibility

Skeptics question whether doughnut principles can be implemented given current power structures. Wealthy interests benefit from the status quo. Fossil fuel companies, major polluters, and financial elites resist changes that might reduce their profits or power.

Proponents respond that climate and ecological crises are making the status quo increasingly untenable. As disruptions intensify, political possibilities expand. The doughnut provides a ready alternative framework when conventional approaches fail.

The Growth Question

Some critics argue that abandoning growth as a goal will lead to economic stagnation, unemployment, and reduced living standards, particularly harming workers and the poor.

Doughnut economists counter that what matters isn't GDP growth but genuine wellbeing, health, education, community, meaning, and ecological stability. Current growth strategies often degrade these dimensions even as GDP rises. Better to directly pursue wellbeing within ecological limits than chase GDP growth that increasingly provides it.

Moreover, technologies and practices that build wellbeing within planetary boundaries, renewable energy, regenerative agriculture, circular economy, care work, can create abundant, meaningful employment.

Implementation Complexity

Moving from theory to practice is extraordinarily complex. Transforming food systems, energy infrastructure, economic institutions, and social norms simultaneously requires coordination across multiple sectors and scales.

This is true, but the alternative, continuing current trajectories, leads to civilizational collapse. The doughnut at least provides a coherent vision to organize transformative efforts. Complexity is a challenge, not a reason to avoid trying.

Why Doughnut Economics Represents Economic Wisdom

What makes Doughnut Economics "wise" rather than just innovative or creative? Several characteristics distinguish it as an expression of genuine wisdom:

Long-Term Thinking

Conventional economics heavily discounts the future, essentially treating the wellbeing of future generations as less important than current consumption. This is foolish, future people matter just as much as we do.

Doughnut Economics explicitly considers planetary boundaries and social foundations across generations. It asks not just "What maximizes welfare now?" but "What enables thriving for centuries to come?"

Systemic Understanding

Wisdom involves seeing connections, understanding relationships, recognizing that everything affects everything else. The doughnut's embedded economy vision—economy within society within biosphere—captures this systemic reality.

Conventional economics treats the economy as separate from nature and society, leading to catastrophic blind spots. Doughnut Economics sees the whole system.

Ethical Clarity

The doughnut begins with clear ethical commitments: everyone deserves to meet their basic needs, and we have no right to destroy the ecological systems that support all life. These aren't disguised technical claims but explicit moral positions.

This ethical clarity provides direction that purely technical economics lacks. It tells us not just how to grow the economy but why, and for whom.

Humility and Adaptation

Doughnut Economics doesn't claim to have all answers or perfect measurements. It offers a framework that communities must adapt to their specific contexts, values, and circumstances.

This humility, recognizing limits to universal formulas, reflects wisdom's acknowledgment that life is complex and local knowledge matters. One-size-fits-all solutions are rarely wise.

Balancing Multiple Needs

Wisdom involves balancing competing goods rather than maximizing single variables. The doughnut explicitly balances social needs with ecological limits, human development with Earth's capacity, individual wellbeing with collective flourishing.

This contrasts with conventional economics' single-minded focus on GDP growth, ignoring trade-offs and assuming growth solves everything.

Learning from Nature

The doughnut's regenerative principles draw on nature's wisdom, billions of years of evolutionary design that creates abundance without waste, diversity without domination, cycles that renew rather than deplete.

Economies that ignore ecological principles are ultimately doomed. Those that learn from nature's patterns can thrive indefinitely.

Practical Steps Toward a Doughnut Economy

Reading about Doughnut Economics might be inspiring, but what can you actually do to help create a wiser economy?

Individual Actions

- Understand your ecological footprint. Calculate your consumption's impact using tools like the Global Footprint Network calculator. Recognize where you're personally overshooting planetary boundaries.

- Shift consumption patterns toward circularity. Buy less, choose quality and durability, repair rather than replace, support companies with regenerative practices, share and borrow instead of owning everything individually.

- Invest and bank differently. Move money to institutions that finance renewable energy, affordable housing, and regenerative agriculture rather than fossil fuels and extractive industries.

- Value care and community. Invest time in relationships, caregiving, and community building, activities that create genuine wellbeing without ecological cost.

Community Level

- Advocate for local doughnut adoption. Contact city officials and suggest your city create a doughnut portrait and action plan. Amsterdam and other cities provide models to follow.

- Support community wealth building. Back local cooperatives, community land trusts, time banks, and other institutions that keep wealth circulating locally and build collective ownership.

- Participate in local food systems. Join community gardens, support farmers markets, participate in community-supported agriculture that connects you directly with regenerative food producers.

- Build commons. Create tool libraries, repair cafes, community workshops, and shared spaces that enable people to meet needs without individual ownership of everything.

Professional and Business Level

- Redesign products and services for circularity. Whatever your industry, ask: How can we eliminate waste? How can we regenerate rather than degrade? How can we measure success by contributions to the doughnut rather than just profit?

- Change metrics. Introduce wellbeing indicators, ecological impact assessments, and doughnut-aligned measures alongside financial metrics. What gets measured gets managed.

- Democratize ownership. Explore employee ownership, cooperative structures, community investment models, and other approaches that distribute ownership and decision-making power.

- Use purchasing power. Organizations can shift procurement toward regenerative suppliers, circular products, and businesses aligned with doughnut principles.

Political Level

- Demand doughnut-aligned policies. Contact representatives to support policies promoting renewable energy, circular economy, progressive taxation, universal basic services, and ecological restoration.

- Change the conversation. Challenge GDP growth as the primary measure of success. Ask: "Will this help people thrive within planetary boundaries?"

- Support systems change. Back candidates and movements working for transformative change, not just incremental adjustments to the status quo.

- Build new institutions. We may need new economic institutions, public banks, participatory budgeting, citizens assemblies, to govern economies for wellbeing rather than growth.

The Future We Could Create

Imagine a world organized around doughnut principles. What might it actually look like?

Cities are green, compact, and powered by renewable energy. Buildings are carbon sinks, materials circulate endlessly, food comes from nearby regenerative farms. Public transit, walking, and cycling make car ownership unnecessary. Everyone has access to beautiful public spaces, affordable housing, and meaningful work.

Work is distributed equitably, with shorter working hours freeing time for care, creativity, and community. Automation reduces drudgery rather than creating unemployment. Cooperatives and employee-owned businesses are common. The distinction between "work" and "life" blurs as people engage in personally meaningful activities that also meet community needs.

Consumption shifts from endless acquisition to sufficiency and quality. Products are designed for decades of use, easily repaired, and eventually returned to manufacturing for new products. Sharing, renting, and borrowing replace individual ownership of rarely-used items. Status comes from contribution, not consumption.

Food systems rebuild soil, draw down carbon, and support biodiversity while producing abundant, nutritious food. Urban gardens, rooftop farms, and nearby agricultural land reconnect people with food production. Seasonal, local eating becomes normal rather than exceptional.

Energy flows from sun, wind, and water rather than fossil fuels. Every building contributes to the energy system. Distributed generation enhances resilience while eliminating pollution.

Economics serves wellbeing rather than growth. Education, healthcare, childcare, and eldercare are recognized as essential to society and supported accordingly. Arts, culture, and community flourishing are valued and resourced. Nature is protected and regenerated as the foundation of all prosperity.

This isn't utopian fantasy, every element exists somewhere today. The challenge is scaling and integrating these pieces into coherent systems.

Economics as if Life Mattered

Doughnut Economics offers something revolutionary yet common-sense: an economic framework that starts with what actually matters, human needs and planetary health, rather than abstract growth imperatives disconnected from wellbeing.

In doing so, it reclaims economics as a tool for creating the world we want rather than accepting the world conventional economics creates.

The doughnut asks a profoundly wise question: What would it take for everyone to thrive without destroying the ecological systems all life depends on? Then it offers a framework for actually answering that question in concrete, practical terms.

This is economics as if life mattered. Economics as if future generations mattered. Economics grounded in ecological reality rather than theoretical fantasy. Economics focused on genuine prosperity rather than endless accumulation.

The transition won't be easy. Powerful interests benefit from the status quo. Inertia is enormous. But the status quo is destroying the conditions for civilized human life. Business as usual guarantees catastrophe.

Doughnut Economics provides an alternative—a vision of what a wise economy could look like and a roadmap for getting there. Whether humanity will follow that road remains uncertain.

But at least now we can see the destination: a world where everyone can thrive within the means of our beautiful, finite, generous planet. A world represented by a simple, profound shape—a doughnut.

The real question is: Are we wise enough to create it?

previous

Elder Voices of the Millennium: Cornel West

next

What Is Consciousness? The Question That Defines What It Means to Be Human

Share this

Sara Srifi

Sara is a Software Engineering and Business student with a passion for astronomy, cultural studies, and human-centered storytelling. She explores the quiet intersections between science, identity, and imagination, reflecting on how space, art, and society shape the way we understand ourselves and the world around us. Her writing draws on curiosity and lived experience to bridge disciplines and spark dialogue across cultures.